My private website. Not visited it yet? Then it is time to do so :D You can find it here. Feedback is greatly appreciated, though I can't guarantee I'll find time to change my site accordingly.

The following essay can also be read as an essay on my website, where it is automatically embedded from this README - and you probably should read it there, because you want to see my website, and there is a table in the README that GitHub doesn't manage to fit into a page somehow ;)

even though it gets no visitors and I don't have the time to make a lot of content for it.

As you would know if I (illegally, for obvious reasons) published tracking data for my website, I haven't really had any visitors since I created it. After all, why would I? There is barely any content on my Website, even if you count the two project cards I added recently, and every other bit of content somewhat meta-heavily resolves around the very essence of my Website.

Then why would I be proud of it?

Because I made a lot of good design decisions, lots of clever engineering, a handfull of innovative solutions, one full-fledged markdown conversion tool, loads of sophisticated optimizations and my own website builder in the process, just to create a website with barely any content yet. In a way, my biggest overkill ever.

And yet I am proud of it! Because I learned a lot in the process, and I created a lot in the process, and I can flex a lot with my Website whenever I find someone willing to listen to me. Which actually is exactly what I will be doing in this essay: Talk about the many design decisions that went into my Website, and how sophisticated it does the hosting of some none-existent essays. Expect this essay to be a little technical, since I am a programmer type of Person, and those tend to refer to code design decisions when they talk about design decisions.

With that being said and the introduction out if our way, let's dive right in into the juicy details! I will go over them using a nestled bullet point list, but that's because these things are easier to navigate than classic paragraphs, so be prepared to read full paragraphs of text within them!

It worth noting for all of these topics that my website is a static website, so there is no server side magic available for any of this.

-

Performant one-page website:

My whole website is served within one single HTML file (including some external resources like CSS, images and javascript, of course). Every link within my website is internal and either calls some javascript (if javascript is enabled), or scrolls to an anchor (if it isn't); more about this later.

Why does it look like there are several pages within the website, then?

In general, my website is divided into one main page, which shows an introduction sentence and a list of all of my projects and my essays, and a multitude of "subpages", which are opened by clicking essay cards on my website, among other things. Each one of my essays, for example, has its own "subpage". When you click on an essay card (and potentially some other things, depending on how this website develops), you immediately, with no loading time save for a quick animation in which the page seems to scroll "up" towards the newly opened subpage, end up on the corresponding subpage. The content of the essay is shown, and a red cross in the upper-right corner appears which you can click to make the essay disappear again, returning you to the main page with another scroll animation.

Opening a subpage not only displays additional content in the window, but also changes several other things associated with switching to another page. The URL in the URL bar changes to something like

phseiff.com/e/name-of-the-essay, the title of the tab changes, and metadata relevant to search engines like the description of the page, the preview image of the page and even its language changes; and vice versa when you leave a subpage. Entering a subpage link likephseiff.com/e/name-of-the-essayinto your browser, vice versa, leads to an empty dummy page that redirects tophseiff.com/#name-of-the-essay, which is then unfolded intophseiff.com/e/name-of-the-essay(the real one, not the dummy) by a bunch of javascript inphseiff.comthat interprets the requested anchor and translates it to a subpage.You might have guessed that this is done using javascript, which is executed every time an essay card is clicked; however, there are some things worth noting here:

-

The content of the essays is hidden until it is unhidden by javascript, but it is not loaded by the javascript.

This is relevant because it means that my website is indeed a single-page-website, and loaded all at once. This means that you can open my website, disable your internet, and still access all of its contents, without having to manually cache every single page of it. It also implies better performance, since having the small overhead of loading some extra kilobyte of essay text (and a bunch of images, whom I might change to javascript-loaden if this becomes too much of a burden later) is much preferable over making separate server requests for every single subpage, each of whom varies only in parts of its content rather than relevant heavy boilerplate code. Having everything within the page at loading time is also relevant for supporting people who disabled javascript, but we will talk some more about that later.

-

Advanced as well as simple crawlers and applications find all subpages, including their metadata.

Advanced crawlers like the ones used by Google for page indexing emulate pages in a headless browser. This allows them to identify javascript-generated subpages, so every subpage (

phseiff.com/e/foo,phseiff.com/e/bar, et cetera) is correctly recognized as its own page, including its title, description, language and contents, as indicated by the javascript-modified meta tags. Google Search Console confirms this works, so ideally, every page should be its own entry in the search engine. In practice, Google only indexes the main page, since it determines the subpages to be "content-identical" to the main page (which is an issue I will have to look into some time), but at least it seems to recognize them as separate entities, according to the Search Console ;)There are also many applications for which a lookup of the page is performed by simply loading the HTML from the page and parsing it, rather than loading the page with a headless browser, which means that these applications will receive the dummy page at

phseiff.com/e/foorather than the contents of the actual subpage. For applications like these, be it crawlers of primitive search engines or a social media platform looking up the OpenGraph protocol metadata of the page, each dummy page contain the metadata of its respective subpage, too. -

The page is fully operational even if javascript is disabled.

It might come as a surprise that all of this works if one has javascript disabled as well. This is implemented by serving the page as a page that works without any javascript at all, and then executing some javascript that modifies it into a page that works based on javascript. This modification to a javascript-based website, since it is based on javascript itself, is only executed if javascript is enabled.

When served, every subpage's content is visible all at once (but below all other elements of the page rather than between the introduction and the essay cards, to ensure the essay cards remain at the top as a table of contents), and each one has its own id so it can be linked to using page-internal anchor links. Analogously, every essay card uses a page-internal link to link its subpage; for example, one essay card might link to

#foo, where#foois the ID of the subpage that is usually accessible viaphseiff.com/e/foo. There are also two arrows, one scrolling to the top and one scrolling to the footer of the page if one clicks them, permanently displayed when javascript is disabled. All of this is obviously not the best user experience, but it allows easy navigation and accessing all the contents of the page even without js. The redirection dummy pages also work with javascript disabled, so even entering the domain of a subpage directly into the browser works as expected with javascript disabled.If javascript is enabled, on the other hand, all of these elements are changed directly when the page loads; subpages are hidden,

#subpage-links are changed to something along the lines ofjavascript:set_location("subpage");,#top-links (and similar ones) are changed to something along the lines ofjavascript:smooth_scroll("top");, the to-the-top and to-the-bottom buttons are hidden unless one is far away from their intended destination, and so on.The non-javascript version of the page is also not exactly optimized for SEO, but that's okay because the biggest relevant search engines all use headless browsers with activated javascript to analyse web pages.

-

-

Writing my own website-builder:

I also wrote my own website builder from scratch in Python. It's a pretty simple one, but I had to do it in order to support my website's architecture.

My website builder does essentially do two things:

-

Maintain the RSS feed and the essay- and project cards on my website.

Both of these things are handled by manually editing an RSS file called

feed-original.rss, which is used for building the essay cards, and a subset of which is used for the actual RSS feed of my website, based on meta-tags that indicate whether an item is intended to be part of the final RSS feed or just a card on my website. -

Maintain the subpages of my website (which is done by manually managing a folder full of markdown files, where

foo.mddescribes the contents of thephseiff.com/e/foosubpage, with no additional action required to be done to add them to my website other than creating them).

There are, of course, some details here, in which I'd like to further dive:

-

Splitting the input of the website builder and the actual website code into separate repositories:

I really want people to see my website's code and potentially profit from it, as well as get attention for it wherever possible (hehe), so my website's code and parts of its website builder are in a public GitHub repository. The markdown files that describe my essays, as well as the html-files immediately generated from them, as well as my RSS feed, are of course also accessible by anyone, because (a) they are embedded into my website, and (b) they are completely hosted, including every bit of code; however, I don't have them in a public repo, because I don't want people looking over my shoulder whilst I work on them, dig through their git history, make pull requests or view my repo out of context, plus I can't be bothered to add the context to which website it belongs to the repository in which I have my website's content.

For this reason, I have my website's content in a private repository, transparent since its contents are hosted via GitHub pages, and simultaneously shielded from the uninterested public. Pushing changes to this repo, as well as seeing (or not seeing) the clock hit 00:00, causes the repo to run an action which builds its RSS feed, converts all markdown files to HTML, and then triggers an action in my public website repo which embeds the subpage's HTML files into the website and builds the essay- and project cards. The public repository also re-builds the website when I push any changes, of course.

-

Maintaining the website's cards and RSS feed:

As mentioned above, I maintain a file called

feed-original.rsswithin my website contents repository. This RSS feed contains information describing the different types of cards on my website, both those that link to subpages ("essay cards") as well as those that link to external pages ("project cards"). The feed, littered with non-standard meta-tags that describe additional contents of the cards, is then parsed into the cards, and a subset (with some items and non-standard tags removed) of the feed is parsed into an actual RSS feed that can be accessed from my website. New subpages also result in a post in my personal mastodon instance.The following table offers some additional details, if you are interested in the exact way I orchestrate my website.

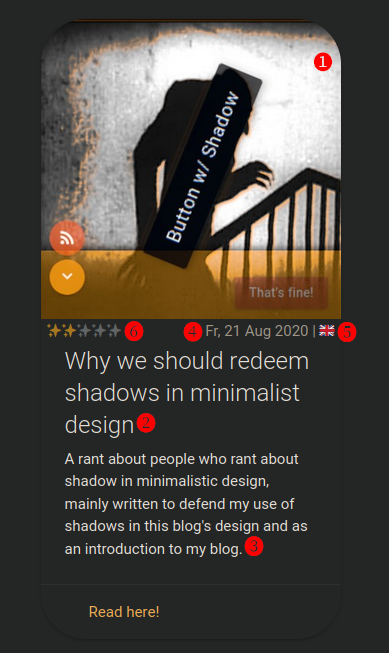

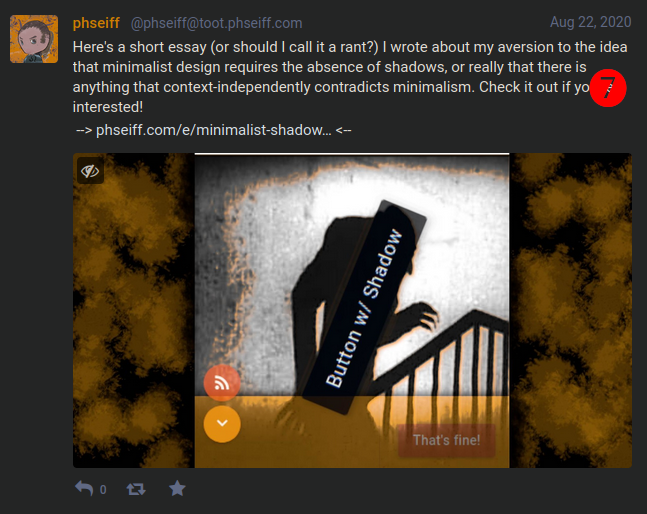

If I add, for example, an entry like the following to

feed-original.rss(<item> <image>❶ https://phseiff.com/phseiff-essays/shadows.jpeg</image> <title>❷ Why we should redeem shadows in minimalist design</title> <description>❸ A rant about people who rant about shadow in minimalistic design, mainly written to defend my use of shadows in this blog's design and as an introduction to my blog.</description> <link>https://phseiff.com/#minimalist-shadows</link> <pubDate>❹ Fr, 21 Aug 2020 18:00:00 +0200</pubDate> <language>❺ en</language> <phseiff:effort>❻ 2/5</phseiff:effort> <phseiff:announcement> ❼ Here's a short essay (or should I call it a rant?) I wrote about my aversion to the idea that minimalist design requires the absence of shadows, or really that there is anything that context-independently contradicts minimalism. Check it out if you're interested! </phseiff:announcement> </item>

), then I get an essay card as shown on this image into my website.

In this format (skip this if the details don't exactly interest you):

- ❶ is the image (I just save

shadows.png, and it is automatically compressed and resized toshadows.jpeg. - ❷ is the title of the essay card

- ❸ is the description on the essay card

- ❹ is the creation date of the content

- ❺ is the language of the content (displayed as a flag)

- ❻ describes how much effort/ confidence I put into/ have in the content, to generate my fancy sparkle rating

- ❼ is a text for announcements and for my RSS feed.

Adding something to the RSS feed also creates a post in my personal Mastodon instance, as can be seen on this image:

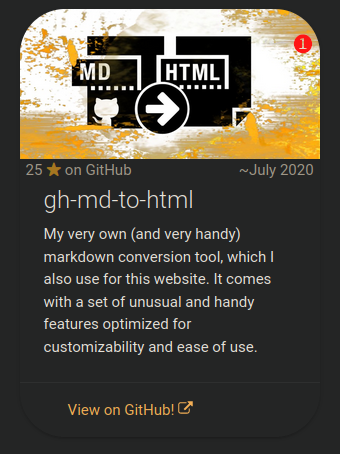

I can also add a

project="true"attribute to any item, in which case the resulting card is added to the project list in my website rather than the essay list, receives a (regularly updated) star count if it links to a GitHub repository rather than language information and a sparkle count, and gets its image build from the repository's preview image, with a fancy orange overlay.The code for this looks, examplary, pretty much like this (

<item project="true"> <image>❶ https://phseiff.com/phseiff-essays/gh-images/github-flavored-markdown-to-html.jpeg</image> <title>❷ gh-md-to-html</title> <description>❸ My very own (and very handy) markdown conversion tool, which I also use for this website. It comes with a set of unusual and handy features optimized for customizability and ease of use.</description> <link>https://github.com/phseiff/github-flavored-markdown-to-html</link> <pubDate>❹ ~July 2020</pubDate> </item>

), where:

- ❶ the image is build from the repository preview image of the repository the card links to;

the rule being that the contents of

https://phseiff.com/phseiff-essays/gh-images/foo.jpegare a compressed JPEG ofgithub.com/phseiff/foo's preview image with an added orange overlay to fit int my website's color scheme. - pretty much everything else is like in every other essay card.

- ❶ is the image (I just save

-

Converting markdown-files to html:

I also wrote a custom markdown-to-html conversion tool for my website, because I wanted to have GitHub README styled subpages whilst still having formula support, which later grow from a tool to inject umlauts into multiline code blocks in GitHub's online markdown API (which GitHub doesn't natively support due to an unfortunate chain of technical limitations) to a tool into which pretty much every markdown converter can be plugged, and which results in GitHub-styled html- and pdf files with some added tweaks and sparkles. This quickly became my so-far biggest tool (🥲), and you can visit it on GitHub if you wanna leave some stardust or, like, actually use it.

Anyways, what I want to talk about here is how it integrates with my building pipeline.

Essentially, every markdown file in my content-repository is thrown into the converter and a html file is generated for each one. All of these have host-ready relative links to all images they reference (a feature of

gh-md-to-html), and all of them share a single css file. In addition, every image any markdown file references is automatically downloaded, stored in a separate folder, converted to progressive JPEG if it isn't one already, receives a mono-colored background, and some compression with some losses. The image is then stored in 10 different resolutions, and all of them are put into the image'ssrcsetattribute, ensuring that the browser loads the minimal resolution that is needed for the given screen size.This allows me to just reference whatever image I use, as a PNG with 3000x2000px, or even images that some ominous source hosts on the web with integrated visitor tracking, without needing to worry about saving the file, compressing it, making different resolutions from that, or having a slow and unsave webpage as an alternative. Another thing worth noting is that since the images are loaded using the

srcsetattribute, thesrcattribute remains free for any use case, so I use it to store the full-size image URL in - this causes Google Images to show the images from my website in their full resolution (including transparency) rather than in their compressed and pixelated form.I think this is a pretty neat feature to have in a markdown converter (I'm not aware of any others with

srcsetsupport), and it makes sure that all these images stay within reasonable bandwidth boundaries.The html pages are then added to a list, which my website builder in my public repo then reads to then proceed to embed every single file into my one-page website as a subpage.

-

-

Auto-generating darkmode with a headless browser:

When I first started working on my website, I intended it to have a dark- as well as a light mode, which adapted to the user's system preference, since I was really big on darkmode back then. I implemented this using DarkReader, which is mainly a browser extension for injecting darkmode into websites using javascript, but also comes with a js-module for use in websites. DarkReader, with the settings I used it with, detects someone's system-wide darkmode-settings and adapts to it by either applying darkmode or not applying darkmode.

However, I quickly noticed that darkreader didn't properly detect darkmode on Chromium on Linux, which sucked because some of my friends used Chromium on Linux, and that I actually don't like how my website looked in lightmode. Plus, the slightly dusty orange that darkreader generated was a nice contrast to the muddy grey it spilled across my website's background, so why not embrace that and make it my brand identity?

I thus changed my website to always use darkmode, no matter the system settings. This left my site with lots of javascript that generated a darkmode on runtime once the site was loaded, resulting in a white flash at the beginning of the loading time and a lot of js execution overhead (around two second, if I recall it correctly).

I ended up building an extra step into my website building pipeline, which emulates the website using a headless browser, and then extracts the css generated by DarkReader from the website with a functionality I specifically asked the maintainer of DarkReader for. The resulting css is then stored in a css file, and all calls to DarkReader that the website contains are replaced with simple links to the generated stylesheet.

This does, admittedly, slow down the pipeline quite a lot (not really problematic, since GitHub action minutes are pretty much free), and it means I can't precisely pick a color because it'll always be shifted by DarkReader, which is problematic if I want a color in my texts to fit a color in an image; but on the other hand, it makes designing color schemes much easier since I can just pick the brightest color available, and it'll always be shifted into a tasteful shady muddy look that goes quite well with all the other colors. For elements I really want to keep their color, I can also just use the HTML

style-attribute, since DarkReader can't create CSS to change them (after all, how should it address the element if there is no query to describe the element?).But let's be honest, the whole thing is a pretty hacky solution, and it's one that adds a lot of technical debt to the whole website and accumulates a lot of hassle when it comes to fine-tuning colors in an essay. Had I anticipated that there wouldn't be a lighmode on the site before I wrote it, I might habe done things differently; but then again, I might not even have this cool harmonic colorscheme I have right now if I had tried to do a darkmode color scheme from scratch.

-

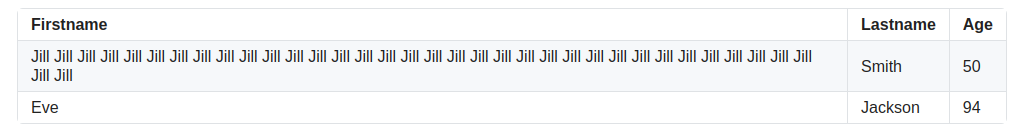

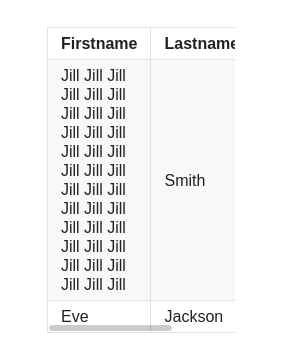

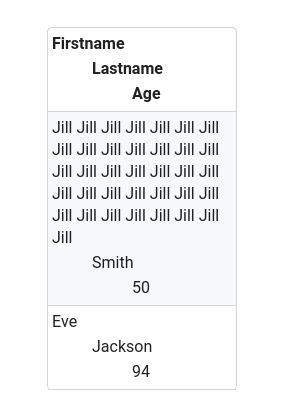

Mobile-friendly tables aka the fanciest tables in the west:

It's a pretty minor thing with quite a minor impact, but it's a pretty special thing and I have never seen another website do this, so here I go including it within my blog post.

When you see a table on a website (e.g. Wikipedia) on desktop, it usually looks somewhat like the following:

If you are on mobile, however, and your screen is small, the table often doesn't fit into the viewport, and ends up overflowing with a nasty horizontal scrollbar, hurting usability and SEO alike.

My website circumvents this problem by adding a special layout for tables that would otherwise overflow, depending on the table's content and the current viewport width, so rather than a crammed table like this (

), the visitors get a table like the following on my website: In case you mind me nerding about the way I implemented this for a while, you can skip to the next section, or look at the relevant file in this website's GitHub repository directly.

Essentially, I wrote two solutions, one with javascript and CSS, and one in pure CSS. As is the case with pretty much everything on my website, the CSS solution is somewhat limited, whilst the javascript solution deactivates the CSS solution (only if javascript is enabled, of course) and replaces it with its own way of doing things.

I will look at both solutions separately in the following:

-

The pure CSS solution:

This uses some pretty simple CSS that re-styles all tables within a query that ensures it's only applied if

screen-size<600px. This comes with the two disadvantages that (1) some tables might be large enough to overflow even ifscreen-size>599px, and (2) all column indents are hard-coded, which means that every field past the 7th field (or so) of a row is not indented at all, and that tables with more than 4 columns (or so) will overflow even with the extra style applied.Both of these issues are fixed by the javascript-implementation.

-

The javascript+CSS solution:

This comes in two steps:

-

As soon as the entire DOM is loaded (even before css and images finished loading), a custom CSS class is created for every table (not yet assigned to it, though). This CSS class describes how the table should look like on a screen on which it'd otherwise overflow, and it contains enough indention levels for all columns, and the indention widths are adjusted to the amount of columns the table has, to make sure no field is indented more than 90px.

This solves issue (2) of the CSS-only solution.

-

Every time the viewport is resized (and one time each after the DOM and the assets of the website are loaded), a function is called (by binding to

DOMContentLoaded,loadedandresizeevents) that iterates over all tables of the document and assigns each one its minify-class (in case it overflows), and un-assigns it again (if doing so is possible without causing an overflow). The pure CSS solution is kept as an intermediate solution through all of this until all images are loaded (triggering theloadevent), to ensure that tables with images in them don't require horizontal scrolling until all images are loaded.This solves issue (1) of the CSS-only solution, and it does so pretty efficiently since it adds no overhead other than a function call on resize and two on page load (the call on

DOMContentLoaded, in case you wondered, isn't really necessary, but it reduces the time until layout shift is finished for subpages without text-only tables).

-

I feel like this way of handling tables should be way more popular than it apparently is (please tell me if you know of any website that does somewhat similar, I'd love to see it!), and I hope you might've found it useful - feel free to use its code, which is mostly MIT licensed.

-

-

Other optimizations & Gadgets I spent way more time on than I probably should have:

-

404 Error page:

I have a neat-looking error page that you might not have seen so far, if you don't happen to manually freestyle-type the address of my so-far only essay into your browser bar on a daily basis (which I wouldn't recommend since it is not the greatest essay).

You can find it at https://phseiff.com/fofobarbar (or any other non-existent URL on my domain, of course).

-

SEO optimization:

I also spent a long time (much, much longer than I probably should have) on optimizing my website for SEO using the Chromium Light House tool, a variety of website speed tests, and some other SEO analysis tools that I won't mention since they decided to become subscription-only tools completely unanticipated. I managed to get into each one's respective "green area" mainly by adding things like title, description, language, OpenGraph-protocol meta tags and TwitterCard meta tags to each one, and by optimizing the page's loading speed by adding automated compression to all images and moving darkmode creation from the website to the website builder.

The results where quite well, although the underlying optimization where extremely premature considering my website's audience (noone who stumbles across it through the web) and its amount of content so far.

-

image compression of images outside the subpages:

All images within my essays are compressed automatically to reduce loading time, as described above. Raster images that aren't part of any essay, but still part of my website, are referenced as JPEG images by the source code, but maintained as full-scale PNG images, and converted to JPEG automatically by my website builder, in case you wondered about the size of this profile image on the top left of my website.

-

fancy image zooming:

Many people like to see images in their full resolution, especially if they intend to save them, which is a problem since all images are by default compressed. Also, many images in my essays are displayed in an image size too small to make out all of their details. Therefore, it is possible to click on any image (you might have noticed the zoom cursor icon when hovering over them), which loads the original uncompressed PNG-image in its full size (potentially not displayed in full size, though, if the display is too small) into the view port, from where it can be copied like any other image (the image is loaded on-demand as to not take any unrequired bandwidth, obviously.

I can also add a

-icon.to the image's file name if I want it to be un-zoomeable, and a-noborder.if I want it to be displayed without the pretty border that surrounds each image. -

ethical tracking:

Since I don't host my webpage myself, but rather, host it on GitHub pages, I can't do server-side visitor counting or anything to see the numbers of my visitors evolve over time. And even if I could, it wouldn't help me much, since I would not be able to see how many people visited which subpage due to the one-page nature of my website.

My solution to this was using a self-hosted tracking service (in my case, Matomo, due to its open source and ethical nature), and make it opt-in on my website - there's a cookie banner that you can remove by opting in, and a detailed explanation of why I use cookies and what I use them for that you can read and reach from the cookie banner.

I originally thought that making the cookie banner stick until one opted in to the tracking was pretty reasonable, since the data is collected anonymously and in reasonable amounts, and nudging people into the direction of being helpful -as an individual, not as a company, mind you- by giving them a better experience if they opt in by removing the cookie banner seemed somewhat logical to me. After all, if I was running an Ice cream parlor, I could also count my visitors without asking for consent, and refusing to let me know one visited me even though I only need it for my own statistics and for improving the things I am working on in itself stroke me as rude enough to plant an unremoveable cookie banner into the visitor's face.

But after some reconsidering and getting exclusively negative feedback from my friends, I realised that people who don't really know me other than from seeing my website have no real reason to trust me, and that even if they could trust me and still decided to not be helpful, paying unhelpfulnes back by being unhelpful oneself is not the best approach as someone who offers something and want people to be convinced of and like that thing.

For this reason, I decided to add a "Nope"-option to my cookie banner, which you can either see in action on my website already or will see in action as soon as I find time to implement it.

That being said, hosting a frickly website analysis tool on one's own infrastructure at home is probably not the most efficient thing to do, especially since it results in large downtimes whenever I carry infrastructure around with me, and matomo is not really optimized for one-page websites, so the way I do it is probably not quite ideal.

But hey, I ask for consent, and I have an option to revoke it, so other from being a nuisance for my visitors, there isn't really anything to criticize here.

-

-

The backside & domain price bragging:

The whole thing is, of course, not always as smooth as I depict it here. Almost every time I write an essay for this website, something turns out not to work like I intended it to work, and every time, I end up tweaking something just to fit that little essay. There are also lots of dirty other things, like generally chaos when it comes to ordering everything into different files, and using whacky push pipelines that automate

git add,git commitandgit pushalongside other things that should be done by GitHub actions, probably (in my defense, at least it's all properly documented, named and throughoutly commented). It's also not the prettiest thing imaginable that I end up putting things like intro texts straight into my website's main template, but hey, that's how it is.On a more positive note, my domain name is quite easy to remember, grippy and handy, and costs me only $18 per year :)

I guess in a way, you could say this essay is me making peace with the fact that I didn't create as much content for my website as I would've liked to in the past 8 months, but it is also, at least partially, me realizing how much I've grown over the past year, both personally and professionally, and how much this website illustrates that and how much there's yet to come.

Anyways, I hope you had fun reading this, and that there were at least a handful of solutions you found interesting, be it positive or negative. :)