- Getting started

- Design goals

- Features

- Integration

- TL;DR

- Usage

- Defaults

- Flags

- Third-party libraries

- License

The quickest way to get started is to download ProgramOptions.hxx as well as one of the samples and go from there.

The default choice. Incorrect usage of ProgramOptions.hxx's API will trigger an assertion which will crash the program in debug mode.

In this sample, we #define PROGRAMOPTIONS_EXCEPTIONS. In consequence, incorrect usage of ProgramOptions.hxx's API will throw an exception both in debug and release mode.

- Non-intrusive. ProgramOptions.hxx requires neither additional library binaries nor integration into the build process. Just drop in the header, include it and you're all set. ProgramOptions.hxx doesn't force you to enable exceptions or RTTI and runs just fine with

-fno-rtti -fno-exceptions. - Intuitive. ProgramOptions.hxx is designed to feel smooth and blend in well with other modern C++11 code.

- Correct. Extensive unit tests and runtime checks contribute to more correct software, both on the side of the user and the developer of ProgramOptions.hxx.

- Permissive. The MIT License under which ProgramOptions.hxx is published grants unrestricted freedom.

- Fully compliant with the GNU Program Argument Syntax Conventions

- Automatic help screen generation

- Automatic error handling

- Spelling suggestions

- Colored console output (can be turned off with

#define PROGRAMOPTIONS_NO_COLORS)

ProgramOptions.hxx adheres to the following rules:

- Short options (

-g) consist of a single hyphen and an identifying character. The character must be graphic (isgraph).- To pass an argument to the option, these syntaxes are allowed:

-O3,-O=3,-O 3 - Multiple short options may be grouped;

-altis equal to-a -l -t. This is only allowed if all options (including the last) don't require an argument.

- To pass an argument to the option, these syntaxes are allowed:

- Long options (

--version) consist of two leading hyphens followed by an identifier. The identifier may consist of alphanumeric (isalnum) characters, hyphens, and underscores but must not start with a hyphen.1- To pass an argument to the option, these syntaxes are allowed:

--optimization=3,--optimization 3

- To pass an argument to the option, these syntaxes are allowed:

- Non-option arguments (

file.txt), also referred to as operands in POSIX lingo or positional arguments, are everything except options and options' arguments. - Short options, long options and non-option arguments can be interleaved at will. Their relative position is retained, i.e. ProgramOptions.hxx does not reorder them.

- A single hyphen

-is parsed as a non-option argument. - Two hyphens

--terminate the option input. Any following arguments are treated as non-option arguments, even if they begin with a hyphen.

1 Note that -version (with only a single hyphen) would be interpreted as the option -v with the argument ersion.

ProgramOptions.hxx is very easy to integrate. After downloading the header file from the include folder and putting it into your project folder, all it takes is a simple:

#include "ProgramOptions.hxx"Don't forget to compile with C++11 enabled, i.e. with -std=c++11.

If you want to integrate ProgramOptions.hxx into your project that uses git, you can write:

git submodule add https://github.com/Fytch/ProgramOptions.hxx third_party/ProgramOptions.hxx

You may replace third_party/ProgramOptions.hxx by any path.

If you want to integrate ProgramOptions.hxx into your project that uses CMake, add the following to your CMakeLists.txt:

add_subdirectory("${CMAKE_CURRENT_LIST_DIR}/third_party/ProgramOptions.hxx")

target_link_libraries(YourExecutable ProgramOptionsHxx)You must replace /third_party/ProgramOptions.hxx by the correct path and YourExecutable by the targets that use ProgramOptions.hxx.

You can then include the header by writing:

#include <ProgramOptions.hxx>Copy and paste this and start hacking:

#include <ProgramOptions.hxx>

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <string>

int main(int argc, char** argv) {

po::parser parser;

std::uint32_t opt = 0;

parser["optimization"]

.abbreviation('O')

.description("set the optimization level")

.bind(opt);

auto& help = parser["help"]

.abbreviation('?')

.description("print this help screen");

std::vector<std::string> files;

parser[""]

.bind(files);

if(!parser(argc, argv))

return -1;

if(help.was_set()) {

std::cout << parser << '\n';

return 0;

}

std::cout << "compiling " << files.size() << " files with O" << opt << '\n';

}Using ProgramOptions.hxx is straightforward; we'll explain it by means of practical examples. All examples shown here and more can be found in the /examples directory, all of which are well-documented.

The following snippet is the complete source code of a simple program expecting an integer optimization level.

#include <ProgramOptions.hxx>

#include <iostream>

int main(int argc, char** argv) {

po::parser parser;

auto& O = parser["optimization"] // corresponds to --optimization

.abbreviation('O') // corresponds to -O

.type(po::u32); // expects an unsigned 32-bit integer

parser(argc, argv); // parses the command line arguments

if(!O.available())

std::cout << "no optimization level set!\n";

else

std::cout << "optimization level set to " << O.get().u32 << '\n';

}And in action:

$ ./optimization

no optimization level set!

$ ./optimization -O2

optimization level set to 2

$ ./optimization -O=0xFF

optimization level set to 255

$ ./optimization -O3 --optimization 1e2

optimization level set to 100

Let's expand on the previous code. We want it to assume a certain value for the option optimization even if the user sets none. This can be achieved through the .fallback(...) method. After parsing, the method .was_set() tells us whether the option was actually set by the user or fell back on the default value.

Furthermore, we want to implement the option -I to let the user specify include paths. Paths should not be converted to any arithmetic type so we simply set the type to po::string.

By calling the method .multi() we're telling the library to store all values, not just the last one. The number of arguments can be retrieved by calling the .size() or the .count() method. The individual values may be read by means of the iterators returned by .begin() and .end(). Bear in mind that these iterators point to instances of po::values so you still need to refer to the correct member, in this case .string. One way of avoiding this is to use the iterators returned by .begin<po::string>() and .end<po::string>() instead. These random-access iterators behave as if they pointed to instances of std::strings. For more information, refer to Example 4.

#include <ProgramOptions.hxx>

#include <iostream>

int main(int argc, char** argv) {

po::parser parser;

auto& O = parser["optimization"] // corresponds to --optimization

.abbreviation('O') // corresponds to -O

.type(po::u32) // expects an unsigned 32-bit integer

.fallback(0); // if --optimization is not explicitly specified, assume 0

auto& I = parser["include-path"] // corresponds to --include-path

.abbreviation('I') // corresponds to -I

.type(po::string) // expects a string

.multi(); // allows multiple arguments for the same option

parser(argc, argv); // parses the command line arguments

// .was_set() reports whether the option was specified by the user or relied on the predefined fallback value.

std::cout << "optimization level (" << (O.was_set() ? "manual" : "auto") << ") = " << O.get().u32 << '\n';

// .size() and .count() return the number of given arguments. Without .multi(), their return value is always <= 1.

std::cout << "include paths (" << I.size() << "):\n";

// Here, the non-template .begin() / .end() methods were used. Their value type is po::value,

// which is not a value in itself but contains the desired values as members, i.e. i.string.

for(auto&& i : I)

std::cout << '\t' << i.string << '\n';

}In action:

$ ./include -I/usr/include/foo -I "/usr/include/bar" -O3

optimization level (manual) = 3

include paths (2):

/usr/include/foo

/usr/include/bar

Up until now, we were missing the infamous --help command. While ProgramOptions.hxx will take over the tedious work of neatly formatting and displaying the options, it doesn't add a --help command automatically. That's up to us and so is adding an apt description for every available option. We may do so by use of the .description(...) method.

But how do we accomplish printing the options whenever there's a --help command? This is where callbacks come into play. Callbacks are functions that we supply to ProgramOptions.hxx to call. After we handed them over, we don't need to worry about invoking them as that's entirely ProgramOptions.hxx' job. In the code below, we pass a lambda whose sole purpose is to print the options. Whenever the corresponding option occurs (--help in this case), the callback is invoked.

The unnamed parameter "" is used to process non-option arguments. Consider the command line: gcc -O2 a.c b.c Here, unlike -O2, a.c and b.c do not belong to an option and neither do they start with a hyphen. They are non-option arguments. In ProgramOptions.hxx, you treat the unnamed parameter like any other option. Options and the unnamed parameter only differ in their default settings.

Note that, in order to pass arguments starting with a hyphen to the unnamed parameter, you'll have to pass -- first, signifying that all further arguments are non-option arguments and that they should be passed right to the unnamed parameter without attempting to interpret them.

#include <ProgramOptions.hxx>

#include <iostream>

int main(int argc, char** argv) {

po::parser parser;

auto& O = parser["optimization"]

.abbreviation('O')

.description("set the optimization level (default: -O0)")

.type(po::u32)

.fallback(0);

auto& I = parser["include-path"]

.abbreviation('I')

.description("add an include path")

.type(po::string)

.multi();

auto& help = parser["help"]

.abbreviation('?')

.description("print this help screen")

// .type(po::void_) // redundant; default for named parameters

// .single() // redundant; default for named parameters

.callback([&]{ std::cout << parser << '\n'; });

// callbacks get invoked when the option occurs

auto& files = parser[""] // the unnamed parameter is used for non-option arguments as in: gcc a.c b.c

// .type(po::string) // redundant; default for the unnamed parameter

// .multi() // redundant; default for the unnamed parameter

.callback([&](std::string const& x){ std::cout << "processed \'" << x << "\' successfully!\n"; });

// as .get_type() == po::string, the callback may take an std::string

// parsing returns false if at least one error has occurred

if(!parser(argc, argv)) {

std::cerr << "errors occurred; aborting\n";

return -1;

}

// we don't want to print anything else if the help screen has been displayed

if(help.was_set())

return 0;

std::cout << "processed files: " << files.size() << '\n';

// .was_set() reports whether the option was specified by the user or relied on the predefined fallback value.

std::cout << "optimization level (" << (O.was_set() ? "manual" : "auto") << ") = " << O.get().u32 << '\n';

// .size() and .count() return the number of given arguments. Without .multi(), their return value is always <= 1.

std::cout << "include paths (" << I.size() << "):\n";

// Here, the non-template .begin() / .end() methods were used. Their value type is

// po::value, which is not a value in itself but contains the desired values as members, i.e. i.string.

for(auto&& i : I)

std::cout << '\t' << i.string << '\n';

}

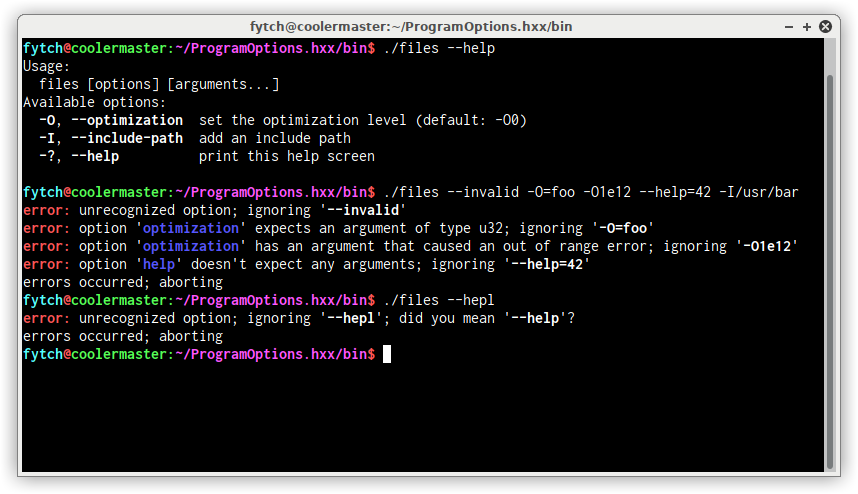

How the help screen appears:

$ ./files --help

Usage:

files.exe [arguments...] [options]

Available options:

-O, --optimization set the optimization level (default: -O0)

-I, --include-path add an include path

-?, --help print this help screen

In action:

$ ./files -I ./include foo.cxx bar.cxx -O3 -- --qux.cxx

processed 'foo.cxx' successfully!

processed 'bar.cxx' successfully!

processed '--qux.cxx' successfully!

processed files: 3

optimization level (manual) = 3

include paths (1):

./include

In this example, we will employ already known mechanics but lay the focus on their versatility.

- Multiple callbacks are invoked in order of their addition.

- For an option of type

po::f64, the possible parameter types of a callback are: <none>,std::string,po::f64_t, or any type that is implicitly constructible from these. - When using C++14,

autoandauto&&are also a valid callback parameter type.

- Fallbacks can be provided in any form that would also suffice when parsed, i.e. also as a

std::string. - If

.multi()is set,.fallback(...)can take an arbitrary number of values.

po::void_: No value, the option has either occurred or notpo::string: Stores the unaltered stringpo::i32/po::i64: Signed integer; supports decimal, hexadecimal (0x), binary (0b) and positive exponents (e0)po::u32/po::u64: Unsigned integer; same as with signed integerspo::f32/po::f64: Floating point value; supports exponents (e0), infinities (inf) and NaNs (nan)

.begin()and.end(): Random-access iterators that point topo::values; thus you have to choose the right member when dereferencing, e.g..begin()->i32.begin<po::i32>()and.end<po::i32>(): Random-access iterators that point to values of the specified type.get(i)(and.size()): Reference topo::value; there's also a.get_or(i, v)method, returning the second parameter if the index is out of range.to_vector<po::i32>(): Returns astd::vectorwith elements of the specified type

#include <ProgramOptions.hxx>

#include <iostream>

#include <numeric>

int main(int argc, char** argv) {

po::parser parser;

auto& x = parser[""] // the unnamed parameter

.type(po::f64) // expects 64-bit floating point numbers

.multi() // allows multiple arguments

.fallback(-8, "+.5e2") // if no arguments were provided, assume these as default

.callback([&]{ std::cout << "successfully parsed "; })

.callback([&](std::string const& x){ std::cout << x; })

.callback([&]{ std::cout << " which equals "; })

.callback([&](po::f64_t x){ std::cout << x << '\n'; });

parser(argc, argv);

std::cout << "(+ ";

for(auto&& i : x.to_vector<po::f64>()) // unnecessary copy; for demonstration purposes only

std::cout << i << ' ';

std::cout << ") = " << std::accumulate(x.begin<po::f64>(), x.end<po::f64>(), po::f64_t{}) << '\n';

}In action:

$ ./sum

(+ -8 50) = 42

$ ./sum 39.5 2.5

successfully parsed 39.5 which equals 39.5

successfully parsed 2.5 which equals 2.5

(+ 39.5 2.5) = 42

$ ./sum 1e3 -1e0 -1e1 -2e2

successfully parsed 1e3 which equals 1000

successfully parsed -1e0 which equals -1

successfully parsed -1e1 which equals -10

successfully parsed -2e2 which equals -200

(+ 1000 -1 -10 -200) = 789

$ ./sum inf -1

successfully parsed inf which equals inf

successfully parsed -1 which equals -1

(+ inf -1) = inf

$ ./sum 12 NaN

successfully parsed 12 which equals 12

successfully parsed NaN which equals nan

(+ 12 nan) = nan

Until now, we defined the type, plurality and fallback value of each option manually by invoking .type, .single/.multi and .fallback. If we just want to extract the values from the parser and store them in a variable, .bind offers a more convenient and safer way of achieving this and ought to be preferred. .bind internally sets the type and the plurality (.single/.multi) of the corresponding option (but not the fallback).

We may bind options to variables of type std::string, to 32- or 64-bit signed integers, unsigned integer, floating point numbers or to STL containers consisting of elements of such type. If we want to use custom container types and/or custom insertion routines, we have to use .bind_container(container&, inserter) which accepts a binary function with the signature inserter(container_t&, container_t::value_type const&) (up to implicit conversion).

#include <ProgramOptions.hxx>

#include <cstdint>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

#include <deque>

#include <iostream>

int main(int argc, char** argv) {

po::parser parser;

std::uint32_t optimization = 0; // the value we set here acts as an implicit fallback

parser["optimization"]

.abbreviation('O')

.description("set the optimization level (default: -O0)")

.bind(optimization); // write the parsed value to the variable 'optimization'

// .bind(optimization) automatically calls .type(po::u32) and .single()

std::vector<std::string> include_paths;

parser["include-path"]

.abbreviation('I')

.description("add an include path")

.bind(include_paths); // append paths to the vector 'include_paths'

auto& help = parser["help"]

.abbreviation('?')

.description("print this help screen");

std::deque<std::string> files;

parser[""]

.bind(files); // append paths to the deque 'include_paths

if(!parser(argc, argv))

return -1;

// we don't want to print anything else if the help screen has been displayed

if(help.was_set()) {

std::cout << parser << '\n';

return 0;

}

// print the parsed values

// note that we don't need to access parser anymore; all data is stored in the bound variables

std::cout << "optimization level = " << optimization << '\n';

std::cout << "include files (" << files.size() << "):\n";

for(auto&& i : files)

std::cout << '\t' << i << '\n';

std::cout << "include paths (" << include_paths.size() << "):\n";

for(auto&& i : include_paths)

std::cout << '\t' << i << '\n';

}Suppresses all communication via stderr. Without this flag, ProgramOptions.hxx notifies the user in case of warnings or errors occurring while parsing. For instance, if an option requires an argument of type i32 and it couldn't be parsed, overflowed or wasn't provided at all, ProgramOptions.hxx would print an error saying that the option's argument is invalid and that it hence was ignored.

This small table helps clarifying the defaults for the different kinds of options.

| Name | "long-option" |

"x" |

"" (unnamed parameter) |

|---|---|---|---|

.abbreviation |

'\0' (none) |

'x' |

❌ (disallowed) |

.type |

po::void_ |

po::void_ |

po::string |

.single / .multi |

.single |

.single |

.multi |

All flags have to be #defined before including ProgramOptions.hxx.

When this flag is set, ProgramOptions.hxx's functions' preconditions are validated with exceptions instead of assertions. If a precondition isn't met, an std::logic_error is thrown whose explanatory strings starts with "ProgramOptions.hxx:N:" where N is the respective line number.

❗ This flag must not vary across different translation units of a single program in order to not violate C++' one definition rule (ODR).

Setting this flag disables all assertions.

❗ This flag must not vary across different translation units of a single program in order to not violate C++' one definition rule (ODR).

Setting this flag disables colored output. On Windows, ProgramOptions.hxx uses the WinAPI (i.e. SetConsoleTextAttribute) to achieve colored console output whereas it uses ANSI escape codes anywhere else.

❗ This flag must not vary across different translation units of a single program in order to not violate C++' one definition rule (ODR).

- Catch for unit testing.

ProgramOptions.hxx is licensed under the MIT License. See the enclosed LICENSE.txt for more information.