In this tutorial, we will install Go and setup our code editor.

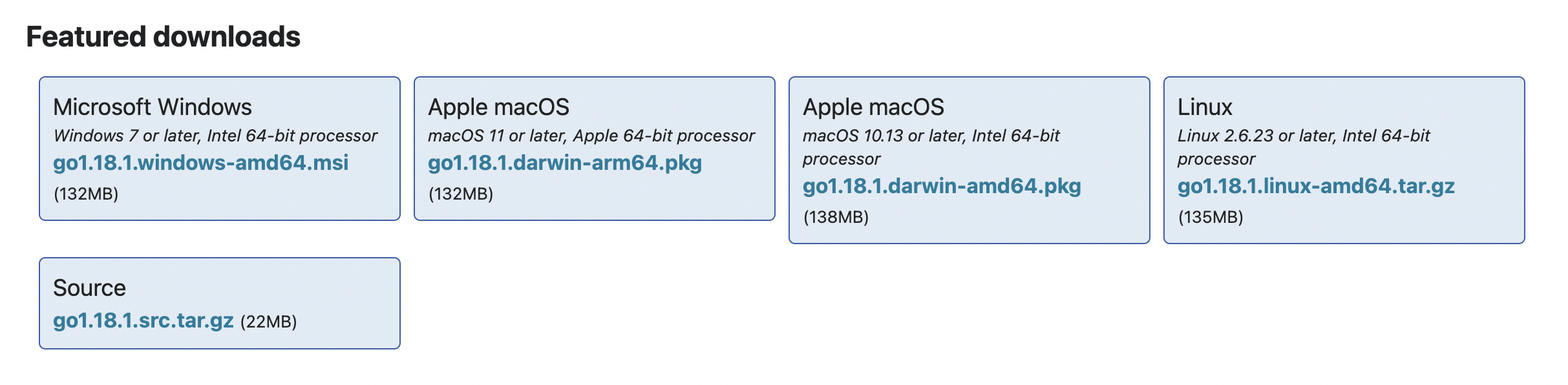

We can install Go from the downloads section.

These instructions are from the official website.

- Open the MSI file you downloaded and follow the prompts to install Go.

By default, the installer will install Go to Program Files or Program Files (x86). You can change the location as needed. After installing, you will need to close and reopen any open command prompts so that changes to the environment made by the installer are reflected at the command prompt.

- Verify that you've installed Go.

- In Windows, click the Start menu.

- In the menu's search box, type cmd, then press the Enter key.

- In the Command Prompt window that appears, type the following command:

$ go version

- Confirm that the command prints the installed version of Go.

Make sure to also install the Go extension which makes it easier to work with Go in VS Code.

This is it for the installation and setup of Go, let's start the course and write our first hello world!

Let's write our first hello world program, we can start by initializing a module. For that, we can use the go mod command.

$ go mod init exampleBut wait...what's a module? Don't worry we will discuss that soon! But for now, assume that the module is basically a collection of Go packages.

Moving ahead, let's now create a main.go file and write a program that simply prints hello world.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

fmt.Println("Hello World!")

}If you're wondering, fmt is part of the Go standard library which is a set of core packages provided by the language.

Now, let's quickly break down what we did here, or rather the structure of a Go program.

First, we defined a package such as main.

package mainThen, we have some imports.

import "fmt"Last but not least, is our main function which acts as an entry point for our application, just like in other languages like C, Java, or C#.

func main() {

...

}Remember, the goal here is to keep a mental note, and later in the course, we'll learn about functions, imports, and other things in detail!

Finally, to run our code, we can simply use go run command.

$ go run main.go

Hello World!Congratulations, you just wrote your first Go program!

Let's start with declaring a variable.

This is also known as declaration without initialization:

var foo stringDeclaration with initialization:

var foo string = "Go is awesome"Multiple declarations:

var foo, bar string = "Hello", "World"

// OR

var (

foo string = "Hello"

bar string = "World"

)Type is omitted but will be inferred:

var foo = "What's my type?"Shorthand declaration, here we omit var keyword and type is always implicit. This is how we will see variables being declared most of the time. We also use the := for declaration plus assignment.

foo := "Shorthand!"Note: Shorthand only works inside function bodies.

We can also declare constants with the const keyword. Which as the name suggests, are fixed values that cannot be reassigned.

const constant = "This is a constant"It is also important to note that, only constants can be assigned to other constants.

const a = 10

const b = a // ✅ Works

var a = 10

const b = a // ❌ a (variable of type int) is not constant (InvalidConstInit)Perfect! Now let's look at some basic data types available in Go. Starting with string.

In Go, a string is a sequence of bytes. They are declared either using double quotes or backticks which can span multiple lines.

var name string = "My name is Go"

var bio string = `I am statically typed.

I was designed at Google.`Next is bool which is used to store boolean values. It can have two possible values - true or false.

var value bool = false

var isItTrue bool = trueOperators

We can use the following operators on boolean types

| Type | Syntax |

|---|---|

| Logical | && || ! |

| Equality | == != |

Signed and Unsigned integers

Go has several built-in integer types of varying sizes for storing signed and unsigned integers

The size of the generic int and uint types are platform-dependent. This means it is 32-bits wide on a 32-bit system and 64-bits wide on a 64-bit system.

var i int = 404 // Platform dependent

var i8 int8 = 127 // -128 to 127

var i16 int16 = 32767 // -2^15 to 2^15 - 1

var i32 int32 = -2147483647 // -2^31 to 2^31 - 1

var i64 int64 = 9223372036854775807 // -2^63 to 2^63 - 1Similar to signed integers, we have unsigned integers.

var ui uint = 404 // Platform dependent

var ui8 uint8 = 255 // 0 to 255

var ui16 uint16 = 65535 // 0 to 2^16

var ui32 uint32 = 2147483647 // 0 to 2^32

var ui64 uint64 = 9223372036854775807 // 0 to 2^64

var uiptr uintptr // Integer representation of a memory addressIf you noticed, there's also an unsigned integer pointer uintptr type, which is an integer representation of a memory address. It is not recommended to use this, so we don't have to worry about it.

So which one should we use?

It is recommended that whenever we need an integer value, we should just use int unless we have a specific reason to use a sized or unsigned integer type.

Byte and Rune

Golang has two additional integer types called byte and rune that are aliases for uint8 and int32 data types respectively.

type byte = uint8

type rune = int32A rune represents a unicode code point.

var b byte = 'a'

var r rune = '🍕'Floating point

Next, we have floating point types which are used to store numbers with a decimal component.

Go has two floating point types float32 and float64. Both type follows the IEEE-754 standard.

The default type for floating point values is float64.

var f32 float32 = 1.7812 // IEEE-754 32-bit

var f64 float64 = 3.1415 // IEEE-754 64-bitOperators

Go provides several operators for performing operations on numeric types.

| Type | Syntax |

|---|---|

| Arithmetic | + - * / % |

| Comparison | == != < > <= >= |

| Bitwise | & | ^ << >> |

| Increment/Decrement | ++ -- |

| Assignment | = += -= *= /= %= <<= >>= &= |= ^= |

Complex

There are 2 complex types in Go, complex128 where both real and imaginary parts are float64 and complex64 where real and imaginary parts are float32.

We can define complex numbers either using the built-in complex function or as literals.

var c1 complex128 = complex(10, 1)

var c2 complex64 = 12 + 4iNow let's discuss zero values. So in Go, any variable declared without an explicit initial value is given its zero value. For example, let's declare some variables and see:

var i int

var f float64

var b bool

var s string

fmt.Printf("%v %v %v %q\n", i, f, b, s)$ go run main.go

0 0 false ""So, as we can see int and float are assigned as 0, bool as false, and string as an empty string. This is quite different from how other languages do it. For example, most languages initialize unassigned variables as null or undefined.

This is great, but what are those percent symbols in our Printf function? As you've already guessed, they are used for formatting and we will learn about them later.

Moving on, now that we have seen how data types work, let's see how to do type conversion.

i := 42

f := float64(i)

u := uint(f)

fmt.Printf("%T %T", f, u)$ go run main.go

float64 uintAnd as we can see, it prints the type as float64 and uint.

Note that this is different from parsing.

Time can be Initialised by Time.Now() method and we can also change the format of the date and time we get by the format methods check the below example to see the evaluation

// time initialization

presentTime := time.Now()

fmt.Println(presentTime)

// to get time in a desired format use like this

fmt.Println(presentTime.Format("01-02-2006 15:04:05 Monday"))

createdDate := time.Date(2020, time.August, 10, 23, 23, 0, 0, time.UTC)

fmt.Println(createdDate)

// to get the random number of type int from 1 to 6 (dice example)

rand.Seed(time.Now().UnixNano());

diceNumber := rand.Intn((6))+1

fmt.Println(diceNumber);

Alias types were introduced in Go 1.9. They allow developers to provide an alternate name for an existing type and use it interchangeably with the underlying type.

package main

import "fmt"

type MyAlias = string

func main() {

var str MyAlias = "I am an alias"

fmt.Printf("%T - %s", str, str) // Output: string - I am an alias

}Lastly, we have defined types that unlike alias types do not use an equals sign.

package main

import "fmt"

type MyDefined string

func main() {

var str MyDefined = "I am defined"

fmt.Printf("%T - %s", str, str) // Output: main.MyDefined - I am defined

}But wait...what's the difference?

So, defined types do more than just give a name to a type.

It first defines a new named type with an underlying type. However, this defined type is different from any other type, including its underline type.

Hence, it cannot be used interchangeably with the underlying type like alias types.

It's a bit confusing at first, hopefully, this example will make things clear.

package main

import "fmt"

type MyAlias = string

type MyDefined string

func main() {

var alias MyAlias

var def MyDefined

// ✅ Works

var copy1 string = alias

// ❌ Cannot use def (variable of type MyDefined) as string value in variable

var copy2 string = def

fmt.Println(copy1, copy2)

}As we can see, we cannot use the defined type interchangeably with the underlying type, unlike alias types.

In this tutorial, we will learn about string formatting or sometimes also known as templating.

fmt package contains lots of functions. So to save time, we will discuss the most frequently used functions. Let's start with fmt.Print inside our main function.

...

fmt.Print("What", "is", "your", "name?")

fmt.Print("My", "name", "is", "golang")

...$ go run main.go

Whatisyourname?MynameisgolangAs we can see, Print does not format anything, it simply takes a string and prints it.

Next, we have Println which is the same as Print but it adds a new line at the end and also inserts space between the arguments.

...

fmt.Println("What", "is", "your", "name?")

fmt.Println("My", "name", "is", "golang")

...$ go run main.go

What is your name?

My name is golangThat's much better!

Next, we have Printf also known as "Print Formatter", which allows us to format numbers, strings, booleans, and much more.

Let's look at an example.

...

name := "golang"

fmt.Println("What is your name?")

fmt.Printf("My name is %s", name)

...$ go run main.go

What is your name?

My name is golangAs we can see that %s was substituted with our name variable.

But the question is what is %s and what does it mean?

So, these are called annotation verbs and they tell the function how to format the arguments. We can control things like width, types, and precision with these and there are lots of them. Here's a cheatsheet.

Now, let's quickly look at some more examples. Here we will try to calculate a percentage and print it to the console.

...

percent := (7.0 / 9) * 100

fmt.Printf("%f", percent)

...$ go run main.go

77.777778Let's say we want just 77.78 which is 2 points precision, we can do that as well by using .2f.

Also, to add an actual percent sign, we will need to escape it.

...

percent := (7.0 / 9) * 100

fmt.Printf("%.2f %%", percent)

...$ go run main.go

77.78 %This brings us to Sprint, Sprintln, and Sprintf. These are basically the same as the print functions, the only difference being they return the string instead of printing it.

Let's take a look at an example.

...

s := fmt.Sprintf("hex:%x bin:%b", 10 ,10)

fmt.Println(s)

...$ go run main.go

hex:a bin:1010So, as we can see Sprintf formats our integer as hex or binary and returns it as a string.

Lastly, we have multiline string literals, which can be used like this.

...

msg := `

Hello from

multiline

`

fmt.Println(msg)

...Great! But this is just the tip of the iceberg...so make sure to check out the go doc for fmt package.

For those who are coming from C/C++ background, this should feel natural, but if you're coming from, let's say Python or JavaScript, this might be a little strange at first. But it is very powerful and you'll see this functionality used quite extensively.

Let's talk about flow control, starting with if/else.

This works pretty much the same as you expect but the expression doesn't need to be surrounded by parentheses ().

func main() {

x := 10

if x > 5 {

fmt.Println("x is gt 5")

} else if x > 10 {

fmt.Println("x is gt 10")

} else {

fmt.Println("else case")

}

}$ go run main.go

x is gt 5We can also compact our if statements.

func main() {

if x := 10; x > 5 {

fmt.Println("x is gt 5")

}

}Note: This pattern is quite common.

Next, we have switch statement, which is often a shorter way to write conditional logic.

In Go, the switch case only runs the first case whose value is equal to the condition expression and not all the cases that follow. Hence, unlike other languages, break statement is automatically added at the end of each case.

This means that it evaluates cases from top to bottom, stopping when a case succeeds. Let's take a look at an example:

func main() {

day := "monday"

switch day {

case "monday":

fmt.Println("time to work!")

case "friday":

fmt.Println("let's party")

default:

fmt.Println("browse memes")

}

}$ go run main.go

time to work!Switch also supports shorthand declaration like this.

switch day := "monday"; day {

case "monday":

fmt.Println("time to work!")

case "friday":

fmt.Println("let's party")

default:

fmt.Println("browse memes")

}We can also use the fallthrough keyword to transfer control to the next case even though the current case might have matched.

switch day := "monday"; day {

case "monday":

fmt.Println("time to work!")

fallthrough

case "friday":

fmt.Println("let's party")

default:

fmt.Println("browse memes")

}And if we run this, we'll see that after the first case matches the switch statement continues to the next case because of the fallthrough keyword.

$ go run main.go

time to work!

let's partyWe can also use it without any condition, which is the same as switch true.

x := 10

switch {

case x > 5:

fmt.Println("x is greater")

default:

fmt.Println("x is not greater")

}Now, let's turn our attention toward loops.

So in Go, we only have one type of loop which is the for loop.

But it's incredibly versatile. Same as if statement, for loop, doesn't need any parenthesis () unlike other languages.

Let's start with the basic for loop.

func main() {

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

fmt.Println(i)

}

}The basic for loop has three components separated by semicolons:

- init statement: which is executed before the first iteration.

- condition expression: which is evaluated before every iteration.

- post statement: which is executed at the end of every iteration.

Break and continue

As expected, Go also supports both break and continue statements for loop control. Let's try a quick example:

func main() {

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

if i < 2 {

continue

}

fmt.Println(i)

if i > 5 {

break

}

}

fmt.Println("We broke out!")

}So, the continue statement is used when we want to skip the remaining portion of the loop, and break statement is used when we want to break out of the loop.

Also, Init and post statements are optional, hence we can make our for loop behave like a while loop as well.

func main() {

i := 0

for ;i < 10; {

i += 1

}

}Note: we can also remove the additional semi-colons to make it a little cleaner.

Lastly, If we omit the loop condition, it loops forever, so an infinite loop can be compactly expressed. This is also known as the forever loop.

func main() {

for {

// do stuff here

}

}In this tutorial, we will discuss how we work with functions in Go. So, let's start with a simple function declaration.

func myFunction() {}And we can call or execute it as follows.

...

myFunction()

...Let's pass some parameters to it.

func main() {

myFunction("Hello")

}

func myFunction(p1 string) {

fmt.Println(p1)

}$ go run main.goAs we can see it prints our message. We can also do a shorthand declaration if the consecutive parameters have the same type. For example:

func myNextFunction(p1, p2 string) {}Now let's also return a value.

func main() {

s := myFunction("Hello")

fmt.Println(s)

}

func myFunction(p1 string) string {

msg := fmt.Sprintf("%s function", p1)

return msg

}Why return one value at a time, when we can do more? Go also supports multiple returns!

func main() {

s, i := myFunction("Hello")

fmt.Println(s, i)

}

func myFunction(p1 string) (string, int) {

msg := fmt.Sprintf("%s function", p1)

return msg, 10

}Another cool feature is named returns, where return values can be named and treated as their own variables.

func myFunction(p1 string) (s string, i int) {

s = fmt.Sprintf("%s function", p1)

i = 10

return

}Notice how we added a return statement without any arguments, this is also known as naked return.

I will say that, although this feature is interesting, please use it with care as this might reduce readability for larger functions.

Next, let's talk about functions as values, in Go functions are first class and we can use them as values. So, let's clean up our function and try it out!

func myFunction() {

fn := func() {

fmt.Println("inside fn")

}

fn()

}We can also simplify this by making fn an anonymous function.

func myFunction() {

func() {

fmt.Println("inside fn")

}()

}Notice how we execute it using the parenthesis at the end.

Why stop there? let's also return a function and hence create something called a closure. A simple definition can be that a closure is a function value that references variables from outside its body.

Closures are lexically scoped, which means functions can access the values in scope when defining the function.

func myFunction() func(int) int {

sum := 0

return func(v int) int {

sum += v

return sum

}

}...

add := myFunction()

add(5)

fmt.Println(add(10))

...As we can see, we get a result of 15 as sum variable is bound to the function. This is a very powerful concept and definitely, a must know.

Now let's look at variadic functions, which are functions that can take zero or multiple arguments using the ... ellipses operator.

An example here would be a function that can add a bunch of values.

func main() {

sum := add(1, 2, 3, 5)

fmt.Println(sum)

}

func add(values ...int) int {

sum := 0

for _, v := range values {

sum += v

}

return sum

}Pretty cool huh? Also, don't worry about the range keyword, we will discuss it later in the course.

Fun fact: fmt.Println is a variadic function, that's how we were able to pass multiple values to it.

In Go, init is a special lifecycle function that is executed before the main function.

Similar to main, the init function does not take any arguments nor returns any value. Let's see how it works with an example.

package main

import "fmt"

func init() {

fmt.Println("Before main!")

}

func main() {

fmt.Println("Running main")

}As expected, the init function was executed before the main function.

$ go run main.go

Before main!

Running mainUnlike main, there can be more than one init function in single or multiple files.

For multiple init in a single file, their processing is done in the order of their declaration, while init functions declared in multiple files are processed according to the lexicographic filename order.

package main

import "fmt"

func init() {

fmt.Println("Before main!")

}

func init() {

fmt.Println("Hello again?")

}

func main() {

fmt.Println("Running main")

}And if we run this, we'll see the init functions were executed in the order they were declared.

$ go run main.go

Before main!

Hello again?

Running mainThe init function is optional and is particularly used for any global setup which might be essential for our program, such as establishing a database connection, fetching configuration files, setting up environment variables, etc.

Lastly, let's discuss the defer keyword, which lets us postpones the execution of a function until the surrounding function returns.

func main() {

defer fmt.Println("I am finished")

fmt.Println("Doing some work...")

}Can we use multiple defer functions? Absolutely, this brings us to what is known as defer stack. Let's take a look at an example:

func main() {

defer fmt.Println("I am finished")

defer fmt.Println("Are you?")

fmt.Println("Doing some work...")

}$ go run main.go

Doing some work...

Are you?

I am finishedAs we can see, defer statements are stacked and executed in a last in first out manner.

So, Defer is incredibly useful and is commonly used for doing cleanup or error handling.

Functions can also be used with generics but we will discuss them later in the course.