This blog post will summarize all the efforts from the Linux community to improve the large-memory allocation over time by looking back at the development history. The key idea is collecting all sorted-by-time blog posts from the LWN.net magazine which related to memory management.

When there are any recent posts or updates on this topic, I will append to the blog and add to the edited history section to easier track.

Since Linux is a virtual memory system, fragmentation normally is not a problem. We can treat memory as a *virtually contiguous* block by the virtual memory mechanism.

Once the system has been running for a while, physical memory is usually fragmented to where very few groups of adjacent, free pages exist. Much work has gone into avoiding the need for *higher-order* (multi-page) memory allocations. As a result, most kernel functionalities still work normally when external fragmentation happens.

However, there can be real performance advantages to using huge pages. On some occasions, using huge pages is unavoidable.

- Reduce pressure on the TLB (Translation Look-aside Buffer) caching. which heavily benefits some applications such as databases.

- large kernel data structures, huge DMA buffer for low-end devices …

In those cases, code that needs such allocations can fail on a fragmented system. Through many years of Linux kernel development, there are many contributions to improve the large-memory allocation on Linux.

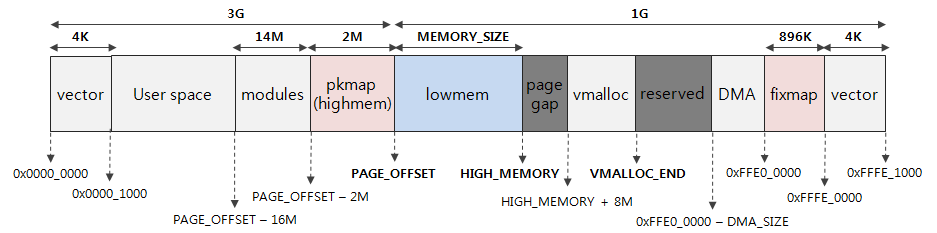

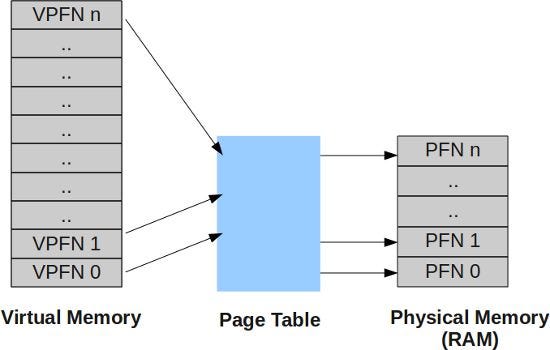

Virtual Memory and Paging

Paging is a memory management scheme that eliminates the need for contiguous allocation of physical memory.

The operating system will have an address translation hardware which uses to translate from the virtual address to the physical address.

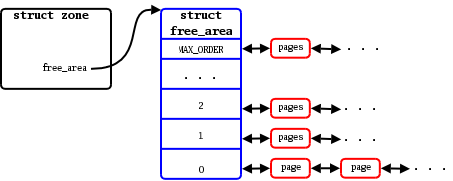

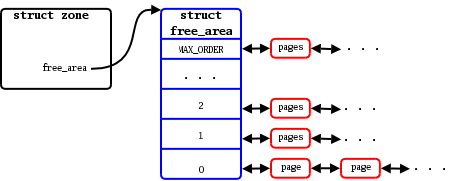

Block Order

Linux manages virtual pages by grouping into the block orders. For each order, there is a linked list of available blocks of that size. For instance, at the bottom of the array, the order-0 list contains individual pages; the order-1 list has pairs of pages, etc.

Memory is grouped into orders for easier in the allocation

High-order allocation

The attempt to get multiple, contiguous pages for an application that needs over one page in a single, physically-contiguous block.

Sometimes, there are enough free virtual pages for the requested memory, but those pages don’t physically contiguous and properly aligned. The system’s memory is fragmented.

Reference: https://lwn.net/Articles/105021/ (October 5, 2004)

Summary

Memory is grouped into orders for easier in the allocation

Sometimes, the system cannot get a block of order-N. The proposed algorithm will collect some pages, then merge to form a block with order-N:

- Start with the largest, smaller blocks we can find.

- Try to move the contents of the pages immediately before and after the block.

- If we can move enough pages, we can merge those free pages into the larger block.

This algorithm seems more complicated when implementing: not all pages can be relocated. e.g.: locked pages, …

Reference: https://lwn.net/Articles/121618/ (February 1, 2005)

Summary

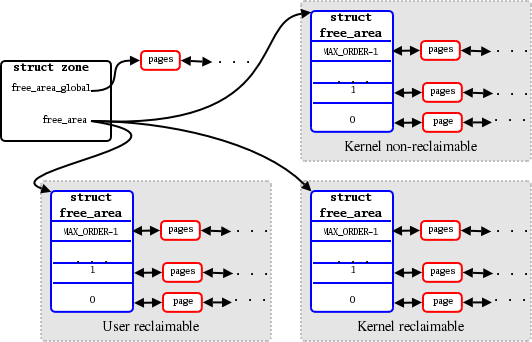

Current architecture:

- The system’s physical memory is split into zones.

- NUMA systems divide things further by creating zones for each node.

- Within each node, memory is split into chunks and sorted depending on its “order”

memory chunks divided into order in each zone

The new approach:

Some types of memory are more easily reclaimed than others. Hence, we group easily-reclaimable pages together, with the non-reclaimable pages grouped into a separate region of memory, it should be much easier to create larger blocks of free memory.

Hence the new improvement is: splitting the memory in each zone into 3 types:

- User reclaimable: expected easily to reclaim.

- Kernel reclaimable: used in caches, which we can drop when need more memory.

- Kernel non-reclaimable: hard to reclaim.

Memory is split into 3 types

Reference: https://lwn.net/Articles/211505/ (November 28, 2006)

Summary

There are 2 improvements.

Improvement 1: Divide the memory into different zones

- Divides each memory zone into three types of blocks: non-reclaimable, easily-reclaimable, and *movable zone* — which is the new type of zone.

- Moveable pages: generally belong to user-space processes. Moving a user-space is just copying the data and updating the table entry.

- Reclaimable pages: usually belongs to the kernel. They are short-lived or can be discarded if needed.

- Everything else is expected hard to reclaim.

- In the stress tests, 80% of memory is available as contiguous blocks at the end of the test. To compare, a standard kernel was getting about 8–12% of memory as large pages at the end of stress tests.

Improvement 2: “Lumpy reclaim” approach — improve the LRU cache

- Originally, the system chooses the next page victim from the LRU list when it needs more memory.

- There is an improvement: The reclaim code looks at *the surrounding pages* of the victim (just *enough to form a higher-order block* to avoid reclaim too many unnecessary pages) and tries to free them as well. In this way, the algorithm will quickly create a larger free block while reclaiming a minimal number of pages.

- This approach works better if the system can free the surrounding pages.

- However, there is a disadvantage: the neighboring pages *may be under heavy use* when the lumpy reclaim code goes after them. Hence, lumpy reclaim should only run when the kernel cannot request a larger block of memory.

Reference: https://lwn.net/Articles/368869/ (January 6, 2010)

Summary

This a nice blog post that introduces a new technique for memory management.

Introduction:

- Sometimes, it is challenged to find *physically contiguous areas of memory* that satisfied 2 conditions: it is big enough and properly aligned.

- There are some various attempts: ZONE_MOVEABLE or lumpy reclaim. However, there is room for improvement, especially in recovering large chunks of memory.

Algorithm illustration

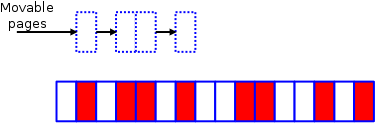

This is the original memory. The white pages are free, while those in red are allocated.

Original fragment

Attempt to acquire a 4-page block will fail. Even a 2-page block will also fail because none of the free pairs of pages are properly aligned.

The compaction code will have 2 separate algorithms.

The first is to start from left to right and build a list of moveable allocated pages.

first half algorithm

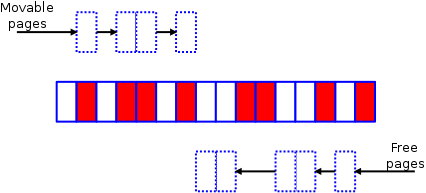

The other half of the algorithm is creating a list of free pages.

second half algorithm

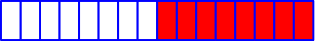

The two algorithms will meet somewhere toward the middle of the zone. After that, the algorithm will shift the used pages to the free space at the top of the zone.

the final result

There are some notes:

- This algorithm only works if pages in action are moveable. *It only takes one non-movable page to ruin a contiguous segment of memory*.

- The good news: the kernel already takes care to separate movable and non-movable pages.

- With compaction enabled, the algorithm could allocate over 90% of the system’s memory as huge pages while simultaneously decreasing the amount of reclaim activity needed.

References: https://lwn.net/Articles/650917/ (July 14, 2015)

Summary

As discussed in the previous section, memory can be defragmented with the memory-compaction algorithm. However, the compaction process is easily interrupted by kernel-allocated pages that cannot be moved out of the way.

- User-space pages are easily migrated. They are accessed via the page tables, so relocating a page is just a matter of changing the page-table entries.

- Pages in the system’s page cache are also accessed via a lookup, so they can be migrated as well.

- Pages allocated by a random kernel subsystem or driver, though, are not so easy to move. They are accessed directly using kernel-space pointers and cannot be moved without changing all of those pointers.

A single unmovable page can foil compaction for a large block of memory. Solving this problem in any given subsystem will require getting that subsystem’s cooperation in the compaction process.

there still has a fair amount of work required to support compaction in an arbitrary kernel subsystem.

Reference: https://lwn.net/Articles/817905/ (April 21, 2020)

Summary

- The kernel is using the *on-demand compaction* approach discussed at [Memory Compaction] section. Whenever there is a request to compact the memory, kcompactd thread is woken up and compacts just enough memory to make available a single page of the needed size.

- This approach often causes a high latency for higher-order allocations. It might affect performance for workloads that need to allocate on many huge pages that happen *at the same time*.

- There is a change in the algorithm: Moving to the *proactive compaction* approach: there is the background job that periodically compacts the memory. There is a discussion here.

- */sys/kernel/mm/compaction/proactiveness* flag: range from [0..100] to determine how aggressively the kernel should compact memory in the background.

- Developers discuss this approach 3 years ago at [Proactive compaction].

Linux's large-memory allocation algorithm has grown for many years.

- Find and merge surrounding smaller blocks into a higher-order block.

- Divide the memory zone into 3 types: Kernel non-reclaimable; Kernel reclaimable; User reclaimable;

- Optimize the types. We divide the memory zone into 3 types: non-reclaimable; easy-reclaimable; moveable;

- Update the LRU cache eviction algorithm: try to evict surrounding pages enough to form a higher-order block.

- Implement the memory compaction algorithm.

- Migrate some kernel pages to the moveable type.

- Implement the proactive memory compaction algorithm.

The development of the large-memory allocation algorithm is still active and we definitely see many enormous changes in the upcoming future.