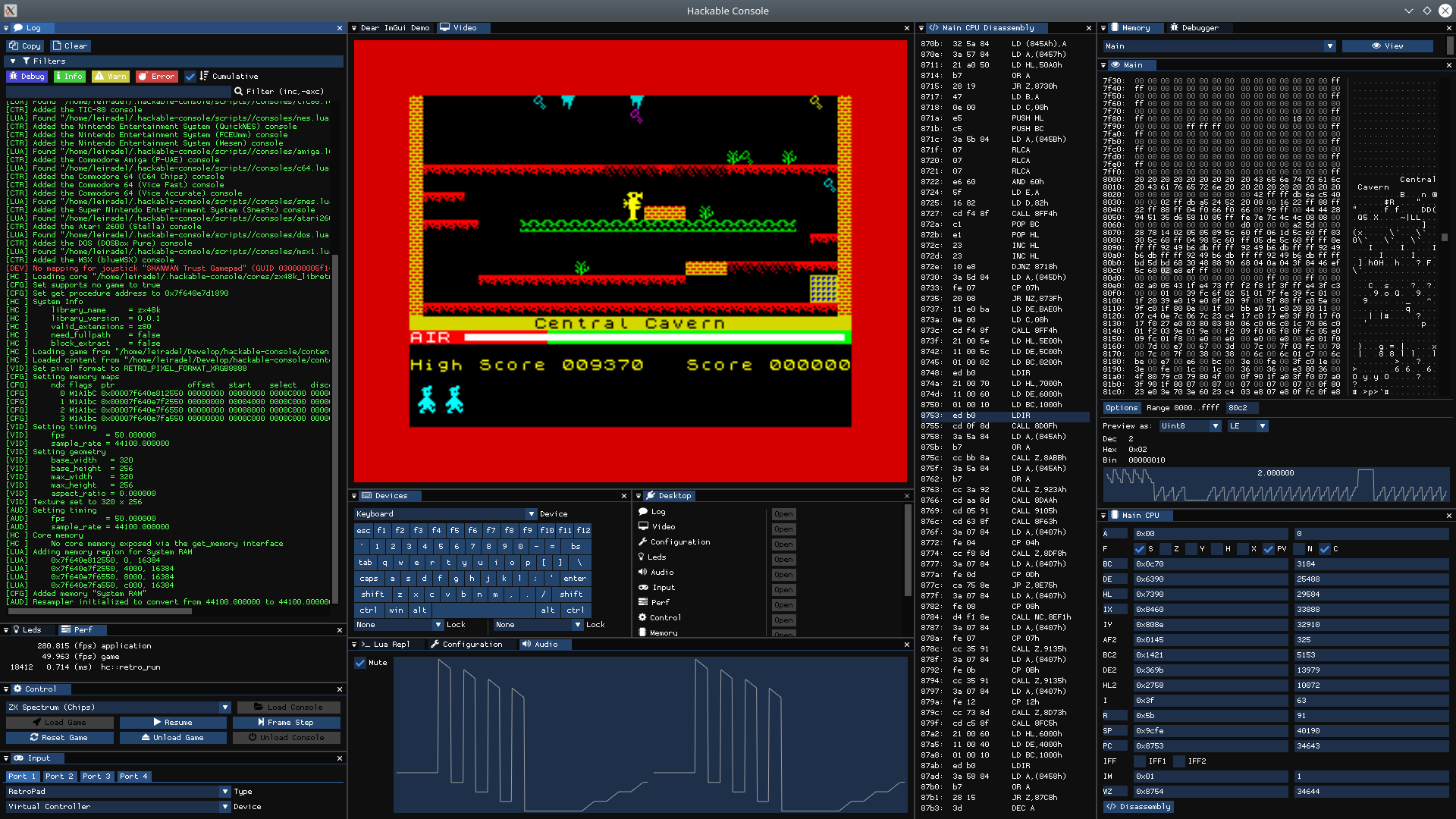

Hackable Console is a pretentious project to add debugging capabilities to Libretro cores, and to create a front-end capable of debugging such cores.

The Libretro API provides a common interface that can be used to write multi-media applications in a multi-platform way. Programs implementing the API as a producer of media are called Libretro cores, and programs that can run those cores are called front-ends.

By creating a Libretro front-end, it's possible to load and run most of the 50+ cores available. The API already supports extensions, so the debug API could be added to the cores, and queried by the front-end.

I believe that this will be much easier than trying to integrate debugging capabilities into stand-alone emulators.

Hackable Console aims to:

- Specify an debug API able to

- Execute of instructions: step-by-step, step into, step out, step over

- Stop execution at certain addresses or when memory is read or written

- Visualize and change the internal CPU state: registers, flags, interruptions

- Disassemble instructions

- Visualize and change memory

- Be versioned so it's easy to add new functionalities

- Implement a Libretro front-end that can load and run Libretro cores, and that implements the debug API. In addition to the regular debugging capabilities provided by the debug API, the front-end also aims to:

- Show symbols instead of addresses where applicable

- Pre-defined symbols available at startup, i.e. ROM routines

- User-defined symbols

- Automatically show important memory regions, such as those pointed to by selected registers, i.e. BC, DE, HL, IX, and IY in the case of the Z80

- Automatically show the system stack, with symbol support

- A cheat engine capable of filtering memory and combining filter results

- Allow external plugins for specific consoles to be loaded and managed by the front-end

- Support scripts

- Snapshots

- Saving and loading of the entire front-end state to support long running reverse-engineering projects

- Show symbols instead of addresses where applicable

- Add the debug API to existing Libretro cores

- To help the development of the debug API and the front-end, zx48k-libretro, a core capable of running ZX Spectrum 48K programs and games, was developed using chips

However, as the project is just starting, the current goal is to implement something that works and that can be used to test the code design both for the debug API and the front-end.

The API consists of just one function that cores must support via retro_get_proc_address_interface: hc_set_debugger. This function will receive a pointer to a hc_Debugger structure, which the core must then fill with the information necessary for the front-end to implement the debugging functionality.

typedef void* (*hc_Set)(hc_DebuggerIf* const debugger_if);I'm a stronger supporter of the "east const" style, for reasons that are better explained elsewhere.

The API is written in C to allow its implementation in as many cores as possible, given the increased inter-operability provided by the language.

typedef struct {

unsigned const frontend_api_version;

unsigned core_api_version;

struct {

/* Informs the front-end that a breakpoint occurred */

void (* const breakpoint_cb)(unsigned id);

/* The emulated system */

hc_System const* system;

}

v1;

}

hc_DebuggerIf;frontend_api_versioncomes in filled by the front-end with the debug API version it supports when thehc_set_debuggerimplementation is called. Only data and functions available inside the structures which versions are less than or equal tofrontend_versionmust be used.core_api_versionmust be filled by the core with the version that it supports. The front-end will never try to access data or functions that the core doesn't support.v1.system: a pointer to ahc_Systemstructure that describes the system being emulated.

It's likely that

hc_DebuggerIfwill be extended to allow more than one system per core, as it's common for emulators to support an entire family of consoles or computers.

hc_System and all other structures from now on must be filled by the core.

typedef struct {

struct {

char const* description;

/* CPUs */

hc_Cpu const* const* cpus;

unsigned num_cpus;

/* Memory regions that aren't addressable by any of the CPUs on the system */

hc_Memory const* const* memory_regions;

unsigned num_memory_regions;

/* Supported breakpoints not covered by specific functions */

hc_Breakpoint const* const* break_points;

unsigned num_break_points;

}

v1;

}

hc_System;v1.description: The system name that the core emulates.v1.cpus: A list of CPUs present in the system. It's not mandatory that all CPUs that compose the system are available in the debug API.v1.num_cpus: The number of CPUs in thecpuslist.v1.memory_regions: A list of memory regions that are not attached to a specific CPU.v1.num_memory_regions: The number of memory regions in thememory_regionslist.v1.break_points: The system-wide breakpoints that can be activated.v1.num_break_points: The number of breakpoints in thebreak_pointslist.

memory_regionshere are used for blocks of memory that are not directly accessible by any of the CPUs, at list not in their entirety, like memory that is banked or only accessible via I/O.

typedef struct {

struct {

/* CPU info */

char const* description;

unsigned type;

int is_main;

/* Memory region that is CPU addressable */

hc_Memory const* memory_region;

/* Registers */

uint64_t (*get_register)(void* ud, unsigned reg);

void (*set_register)(void* ud, unsigned reg, uint64_t value);

unsigned (*set_reg_breakpoint)(void* ud, unsigned reg);

/* Any one of these can be null if the cpu doesn't support the functionality */

void (*step_into)(void* ud); /* step_into is also used to step a single instruction */

void (*step_over)(void* ud);

void (*step_out)(void* ud);

/* set_break_point can be null when not supported */

unsigned (*set_exec_breakpoint)(void* ud, uint64_t address);

/* Breaks on read and writes to the input/output address space */

unsigned (*set_io_watchpoint)(void* ud, uint64_t address, uint64_t length, int read, int write);

/* Breaks when an interrupt occurs */

unsigned (*set_int_breakpoint)(void* ud, unsigned type);

/* Supported breakpoints not covered by specific functions */

hc_Breakpoint const* const* break_points;

unsigned num_break_points;

}

v1;

}

hc_Cpu;v1.description: The CPU description, i.e. Zilog Z80.v1.type: The particular CPU model, so that the front-end knows how to disassemble instructions etc.v1.is_main: True (!=0) if this is the main CPU in the system.v1.memory_region: The memory region accessible by the CPU.v1.get_register: Gets the value of a register. In the case of the Z80, not all emulators can correctly emulate the WZ register, in this caseget_registershould return zero.v1.set_register: Sets the value of a register.v1.set_reg_breakpoint: Sets a breakpoint that triggers when the register's value changes.v1.step_into: Executes a single instruction for the CPU. If the instruction is a call, execution continues in the called address.v1.step_over: Executes a single instruction for the CPU. If the instruction is a call, execution will be resumed until the callee returns.v1.step_out: Resumes execution until control is returned to the caller, e.g. via aRETinstruction in the Z80 case.v1.set_exec_breakpoint: Sets a breakpoint that triggers when the given address is executed. Only the actuall address of the instruction can trigger the breakpoint, i.e. setting a breakpoint to the address of an operand won't work.v1.set_io_watchpoint: Sets a breakpoint that triggers when an I/O port in the given range is read and/or written.v1.set_int_breakpoint: Sets a breakpoint that triggers when an interrupt is served by the CPU.v1.break_points: A list of other breakpoints supported by the CPU, i.e. an exception condition that is not an interrupt.v1.num_break_points: The number of breakpoints in thebreak_pointslist.

memory_regionhere reflect exact what the CPU sees when it reads bytes. As an example, a banked cartridge won't appear in its entirety here, only the banks that are currently selected to be visible via the CPU address bus.

Many games written in assembly employ tricks to save either memory space, CPU cycles, or both. Sometimes when an address is called, the callee won't return to the instruction following the

CALLinstruction. The core must be careful to implementstep_overandstep_outto support the required functionality as best as possible. In any case, the core must never lock into an execution loop that prevents the user from interacting with the front-end.

typedef struct {

struct {

char const* description;

unsigned alignment; /* in bytes */

uint64_t base_address;

uint64_t size;

uint8_t (*peek)(void* ud, uint64_t address);

/* poke can be null for read-only memory but all memory should be writeable to allow patching */

/* poke can be non-null and still don't change the value, i.e. for the main memory region when the address is in rom */

void (*poke)(void* ud, uint64_t address, uint8_t value);

/* set_watch_point can be null when not supported */

unsigned (*set_watchpoint)(void* ud, uint64_t address, uint64_t length, int read, int write);

/* Supported breakpoints not covered by specific functions */

hc_Breakpoint const* const* break_points;

unsigned num_break_points;

}

v1;

}

hc_Memory;v1.description: The description of the memory region.v1.alignment: The alignment of the memory region. This can be used by the front-end to decide how to show the memory in an editor.v1.base_address: Where in the CPU address space the region begins. As an example, a MSX cartridge has a base address of0x4000.v1.size: The size of the region.v1.peek: A function that can read bytes from the memory region. The address will be inside thebase_address-base_address + size - 1range.v1.poke: A function that can write bytes to the region. ROMs should support writes to allow patches.v1.set_watch_point: Sets a watchpoint at the given block of region, starting ataddressand going forlengthbytes. The watchpoint can be triggered for reads, writes, or both.v1.break_points: A list of other breakpoints supported by the memory, i.e. if the read is contended.v1.num_break_points: The number of breakpoints in thebreak_pointslist.

A 256 KiB MegaROM MSX cartridge (a cartridge that has banking) can be exposed via two different memory regions, one that begins at

0x4000and has a size of 32 KiB, and that always reflect what the CPU can see via its address bus and has theHC_CPU_ADDRESSABLEbit set, and another that begins at address 0 and has a size of 256 KiB, which is the entire contents of the cartridge, and that does not have theHC_CPU_ADDRESSABLEbit set as the CPU is not capable of accessing the contents of the entire 256 KiB range via its address bus.

During development, support for the Z80 is being coded.

/* Supported CPUs in API version 1 */

#define HC_CPU_Z80 HC_MAKE_CPU_TYPE(0, 1)

/* Z80 registers */

#define HC_Z80_A 0

#define HC_Z80_F 1

#define HC_Z80_BC 2

#define HC_Z80_DE 3

#define HC_Z80_HL 4

#define HC_Z80_IX 5

#define HC_Z80_IY 6

#define HC_Z80_AF2 7

#define HC_Z80_BC2 8

#define HC_Z80_DE2 9

#define HC_Z80_HL2 10

#define HC_Z80_I 11

#define HC_Z80_R 12

#define HC_Z80_SP 13

#define HC_Z80_PC 14

#define HC_Z80_IFF 15

#define HC_Z80_IM 16

#define HC_Z80_WZ 17

#define HC_Z80_NUM_REGISTERS 18

/* Z80 interrupts */

#define HC_Z80_INT 0

#define HC_Z80_NMI 1The front-end works with the concept of Consoles. Consoles are specific Libretro cores that implement the debug API, and that have an companion Lua script that is responsible for its loading and required configuration and/or automation.

The Lua script is required because some cores have specific needs to be considered ready to be debbuged, i.e.:

- Concatenate different memory regions or descriptors into one single memory view

- Configure some aspects of the core so that it works best with the front-end, i.e. configure the core for software rendering

Some technology that is used:

- SDL to abstract a bunch of stuff

- SDL_GameControllerDB to support as many as possible game controllers in the front-end

- Dear ImGui for the GUI

- A file system widget from here

- This patched version of

imgui_memory_editor - ImGuiAl for some widgets

- IconFontCppHeaders for macros that make it easy to use the icons provided by Font Awesome

- lrcpp to make it easier to write a fully functional Libretro front-end

- Speex to resample the audio output from the cores to the sample rate required by the host system

- fnkdat to provide a platform-independent way of computing and creating some folders needed by the front-end

- This library is old so I'm open to ideas for replacements

dynlibfor a platform-independent way of loading shared objects and getting their symbols- I've been using this for a long time and I can't seem to track down the original source, if you're the author and the license is not compatible with the one used here (MIT), please contact me

- Lua 5.4.2 as the scripting language

- LuaFileSystem to provide the scripts the ability to discover and run other scripts

- ddlt for its Finite State Machine compiler that is used to generate a class from

LifeCycle.fsmthat guarantees the application is always in a consistent status. - I'm currently using chips for its Z80 disassembler, but I'll likely have to write a custom one that can use symbols instead of only addresses

The language used for the front-end is C++, and I'm employing multiple-inheritance as a way to allow classes to implement multiple interfaces, where an interface is an abstract C++ class. For all the criticism that multiple-inheritance gets, for this project I believe that it's working quite well. IMO the real issue with OOP is a deep hierarchy tree (not counting issues like cache which I'm not worried about in this project). Everything is declared in the hc namespace.

The Front-end has the concept of a desktop, where multiple views can be added and laid out.

Some notes about the code:

Desktop.h- Declares the

Viewinterface.- Views must have a title, and have methods that follow the application life-cycle.

- Classes that implement this interface can be added to the desktop.

- Declares the

Desktopclass, which is itself aView.Desktophas a method to add views for it to manage.- It has helpers to access the logging system because it makes it easier for views to log things as they all have a parent desktop property.

- It also has methods to compute the draw FPS, which is the FPS of the front-end so to speak, and the frame FPS, which is the FPS of the core.

- The only class that inherits from

DesktopisApplication.

- Declares the

Scriptable.h- Declares the

Scriptableinterface.- This interface has only one method,

push, which must push an instance of a class that implements it onto the Lua stack as a full userdata object. - Classes that implement this interface should also have a method that can check if an instance of it is present at a particular index of the Lua stack, i.e.

static Config* check(lua_State* const L, int const index); - I'm not convinced of the necessity of this interface, but it'll stay there for now.

- This interface has only one method,

- Declares the

Application.h- Declares the

Applicationclass which is the main class of the front-end.Applicationimplements bothDesktopandScriptable- As the aggregator of all the front-end functionality, its

pushmethod will push all other scriptable objects present in the system:logger,config,led,perf,control, as well as some additional information commonly found in Lua modules. Applicationis not a singleton, but it should be. I'm not very keen of singletons, but it made sense to write the main application code in a class, and there should be only one instance of it at a time.- This class is responsible for initializing everything: SDL, ImGui, and instantiate the views that are always available.

- It's also responsible for the event loop and system tear down.

- Application is the context used with the Finite State Machine that manages the application life-cycle, and thus implements all the methods that the FSM needs to change its state.

- Declares the

Timer.h- Implements a timer that can be paused and resumed, used to compute FPS metrics in the desktop. Shamelessly copied from the Lazy Foo implementation.

Fifo.h- Implements a byte ring buffer used by the audio subsystem to help with audio resampling and sending to the hardware audio device

Devices.hDeviceis aViewthat abstracts input devices for the rest of the system- Has a keyboard device, usable by both the physical keyboard and via a On-Screen Keyboard widget

- Has a mouse device, which is the physical mouse but constrained by the video texture so it's usable by the Libretro core

- Has a virtual game controller usable via the physical keyboard

- Manages all connected game controllers, including hot-plugging

- Classes wanting to know when devices are added to and removed from the system can implement the

DeviceListenerinterface and add themselves to theDeviceinstance

lrcppcomponentsLogger.h: Declares theLoggerimplementation. The logger is also aViewandScriptable.Config.h: Declares theConfigimplementation.Configalso implementsViewandScriptable.Configis also responsible for declaring memory views using the concatenation of different memory regions or descriptors made available by the core, which can be done in a Lua script.

Video.h: Declares theVideoimplementation.Videois a view, and uses OpenGL to keep a texture updated in respect to the emulated framebuffer and blit it via ImGui.Led.h: Declares theLedimplementation. Led is also aViewandScriptableso Lua can use leds to signal state if they want. Thislrcppcomponent is a minor one, but the Vice Libretro core crashes if there's not one available.Audio.h: Declares theAudioimplementation, which is also aViewthat renders the audio frames as a wave form. Not particularly useful but interesting to watch.Input.h: Declares theInputimplementation, which is also aViewand aDeviceListener.Perf.h: Declares thePerfimplementation.Perfalso implementsView(so it's possible to see the registered counters), andScriptable(so it's possible to perf Lua code)Applicationautomatically creates a counter around the Libretroretro_runfunction call

- Other components are not implemented for now

- Other views

Control.h: Has a GUI to allow the control of the application lifecycle: open a core, open a game, run, pause, and resume the game, unload it, and unload the core. It's also scriptable, and provides Lua methods to call into the Libretro API implemented by the core.Cpu.h- Has the

DebugMemoryview which implements theMemoryinterface for memory regions published by the core via the debug API. - Has the

Cpuinterface, which is a view with a couple of additional abstract methods. Each CPU type supported by the core must implement this interface, andCpu::createmust be changed to create and return the actual instance for a CPU type.

- Has the

Debugger.h- Has the

Debuggerview, which can be used to open a view for one of the CPUs present in the emulated system. - Has the

Disasmview, which presents the disassembly of the code surrounding the CPU's program counter. Must be extended to support scrolling to arbitrary addresses.

- Has the

Memory.h- Declares the

Memoryinterface, which must be implemented by anyone wanting to present an edit control for a block of memory as a hexadecimal view. - Has the

MemoryWatchview, which shows an edit control for aMemory. - Has the

MemorySelectorview, which centralizes allMemoryinstances and allows them to be opened in aMemoryView.

- Declares the

- The rest

LifeCycle.fsm: May appear small and unnecessary, but is central in making sure the application is always in a consistent state. One of the biggest challenges and source of bugs in any medium-sized application IMO.LuaUtil.h: Some utility stuff to use with Lua