-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 85

Filesystems

- Filesystems

/home is where another mount point should be if you are fault

tolerant - Bhuvy

Filesystems are important because they allow you to persist data after a computer is shut down, crashes, or has memory corruption. Back in the day, filesystems were expensive to use. Writing to the filesystem or FS involved writing to a magnetic tape and reading from that tape TODO: citation needed. It was slow, heavy, and prone to errors.

Nowadays most of our files are stored on disk – though not all of them! The disk is still slower than memory by an order of magnitude or two TODO: citation needed

Some terminology before we begin this chapter. A filesystem as we’ll define later is anything that satisifies the API of a filesystem, it may not be a hard disk. A disk is either a HDD or Hard Disk Drive which includes a spinning metallic platter and a head which can zap the platter to encode a 1 or a 0, or an SSD or Solid State Drive that can flip certain NAND gates on a chip or standalone drive to store a 1 or a 0. As of 2019, SSDs are an order of magnitude faster than the standard HDD. These are typical backings for a filesystem. A filesystem is implemented on top of this backing, meaning that we can either implement something like EXT, MinixFS, NTFS, FAT32 etc on a commercially available hard disk. This filesystem tells the operating system how to organize the 1s and 0s to store file information as well as directory information, but more on that later.

The last piece of background is an important one. In this chapter, we will refer to sizes of files in the ISO-compliant KiB or Kebibyte. The *iB family is short for power of two storage. That means the following

KiB = 1024B

MiB = 1024 * 1024 B

GiB = 1024^3 B

...

And the standard notational prefixes mean the following.

KB = 1000B

MB = 1000 * 1000 B

GB = 1000^3 B

...

We will do this in the book and in the networking chapter to keep consistency and not to confuse anyone. What will be confusing is that in the real world there is a convention. That convention is that when a file is stored on a traditional file system, KB is the same as KiB. When we are talking about computer networks KB is not the same as KiB and is the ISO/Metric Definition above. This is a historical quirk was brought by a clash between network developers and memory/hard storage developers. Hard storage and memory developers found that if a bit could take one of two states, it would be naturally to call a Kilo- prefix 1024 because it was about 1000. Network developers had to deal with bits, real time signal processing, and various other factors so they went with the already accepted convention that Kilo- means a 1000 of something TODO: citation needed. What you need to know is if you see KB in the wild, that it may be 1024 based on the context. If any time in this class you see KB or any of the family refer to a filesystems question, you can safely infer that they are referring to 1024 as the base unit.

You may have encountered the old unix adage, "everything is a file". In most UNIX systems, files operations provide an interface to abstract many different operations. Network sockets, hardware devices and even data on disk are all represented by a file-like object. A file-like object must follow certain conventions:

-

It must present it self to the filesystem

-

It must support common filesystem operations, such as

open,read,write

A filesystem is an implementation of the file interface. In this chapter, we will be exploring the various callbacks a filesystem provides and some typical functionality or implementation details associated with this. In this class, we will mostly talk about filesystems that serve to allow users to access data on disk. These filesystems are integral to modern computers. Filesystems not only deal with storing local files, they handle special devices that allow for safe communication between the kernel and user space. Filesystems also deal with failures, scalability, indexing, encryption, compression and performance. Filesystems handle the abstraction between a file which contains data and how exactly that data is stored on disk, partitioned, and protected.

Although filesystems are usually thought of as a kind of tree, most filesystems are usually a directed graph, a model we will explore in depth later in this chapter. Before we dive into the details of a filesystem, let’s take a look at some examples.

-

ext4Usually mounted at /, this is the filesystem that usually provides disk access as you’re used to. -

procfsUsually mounted at /proc, provides information and control over processes. -

sysfsUsually mounted at /sys, a more modern version of /proc that also allows control over various other hardware such as network sockets. -

tmpfsMounted at /tmp in some systems, an in-memory filesystem to hold temporary files. -

sshfsA filesystem that syncs files across the ssh protocol.

To clarify, a mount point is simply a mapping of a directory to a

filesystem represented in the kernel. What this means is that to resolve

which filesystem a structure a call must resolve to. Meaning that

/root is resolved by the ext4 filesystem in our case, but /proc/2

is resolved by the procfs system even though it contains / as a

subsystem.

As you may have noticed, some of these filesystems provide an interface

to things that aren’t a "file" as you might colloquially refer to them.

Filesystems such as procfs are usually referred to as virtual

filesystems, since they don’t provide data access in the same sense as a

traditional filesystem would. Technically, all filesystems in the kernel

are represented by virtual filesystem, but in our class we will

differentiate virtual filesystems as filesystems that actually don’t

store anything on a hard disk.

A filesystem must provide callback functions to a variety of actions. Some of them as listed below:

-

openOpens a file for IO -

readRead contents of a file -

writeWrite to a file -

closeClose a file and free associated resources -

chmodModify permissions of a file -

ioctlInteract with device parameters of character devices such as terminals

Not every filesystem supports all the possible callback functions. For

example many filesystems do not implement ioctl or link. In this

chapter, we will not be examining each filesystem callback. If you would

like to learn more about this interface, try looking at the

documentation for FUSE, the source code for glibc or the linux man

pages.

In order to understand how a filesystem interacts with data on disk, there are three key terms we will be using.

-

disk blockA disk block is a portion of the disk that is reserved for storing the contents of a file or a directory. -

inodeAn inode is a file or directory. This means that an inode contains metadata about the file as well as pointers to disk blocks so that the file can actually be written to or read from. -

superblockA superblock contains metadata about the inodes and disk blocks. An example superblock can store how full each disk block is, which inodes are being used etc. Modern filesystems may actually contain multiple superblocks and a sort-of super-super block that keeps track of which sectors are governed by which superblocks. This tends to help with fragmentation.

These structures all are presented in the diagram below.

It may seem overwhelming, but by the end of this chapter, we will be able to make sense of every part of the filesystem.

In order to reason about data on some form of storage (spinning disks, solid state drives, magnetic tape, etc.), it is common practice to first consider the medium of storage as a collection of blocks. A block can be thought of as a contiguous region on disk, and while it’s size is sometimes determined by some property of the underlying hardware, it is more frequently determined based off of the size of a page of memory for a given system, so that data from the disk can be cached in memory for faster access - a very important feature of many filesystems.

Usually, a filesystem has a special block denoted as a superblock which stores metadata about the filesystem such as a journal (which logs changes to the filesystem), a table of inodes and where the first inode is stored on disk, etc. The important thing about a superblock is that it is in a known location on disk.

The inode is the most important structure for our filesystem as it represents a file. Before we explore it in depth, let’s list out the key information we need to have a usable file:

-

Name

-

File size

-

Time created, last modified, last accessed

-

Permissions

-

Filepath

-

Checksum

-

File data

From http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inode:

In a Unix-style file system, an index node, informally referred to as an inode, is a data structure used to represent a filesystem object, which can be one of various things including a file or a directory. Each inode stores the attributes and disk block location(s) of the filesystem object’s data. Filesystem object attributes may include manipulation metadata (e.g. change, access, modify time), as well as owner and permission data (e.g. group-id, user-id, permissions).

Typically, the superblock stores an array of inodes, each of which stores direct, and potentially several kinds of indirect pointers to disk blocks. Since inodes are stored in the superblock, most filesystems have a limit on how many inodes can exist. Since each inode corresponds to a file, this is also a limit on how many files that filesystem can have. Trying to overcome this problem by storing inodes in some other location greatly increases the complexity of the filesystem. Trying to reallocate space for the inode table is also infeasible since every byte following the end of the inode array would have to be shifted, a highly expensive operation. This isn’t to say there aren’t any solutions at all, although typically there is no need to increase the number of inodes since the number of inodes is usually sufficiently high.

Big idea: Forget names of files: The ‘inode’ is the file.

It is common to think of the file name as the ‘actual’ file. It’s not! Instead consider the inode as the file. The inode holds the meta-information (last accessed, ownership, size) and points to the disk blocks used to hold the file contents. However, the inode does not usually store a filename. Filenames are usually only stored in directories. (see below)

For example, to read the first few bytes of the file, follow the first direct block pointer to the first direct block and read the first few bytes. Writing follows the same process. If you want to read the entire file, keep reading direct blocks until you’ve read a number of bytes equal to the size of the file. If the total size of the file is less than that of the number of direct blocks multiplied by the size of a block, then unused block pointers will be undefined. Similarly, if the size of a file is not a multiple of the size of a block, data past the end of the last byte in the last block will be garbage.

What if a file is bigger than the maximum space addressable by it’s direct blocks?

“All problems in computer science can be solved by another level of indirection.” - David Wheeler

Except the problem of too many layers of indirection.

To solve this problem, we introduce the indirect blocks. An indirect block is a block that store pointers to more data blocks. Similarly a double indirect block stores pointers to indirect blocks and the concept can be generalized to arbitrary levels of indirection. This is a very important concept, since as inodes are stored in the superblock, or some other structure in a well known location with a constant amount of space, indirection allows exponential increases in the amount of space an inode can keep track of.

As a worked example, suppose we divide the disk into 4KiB blocks and we want to address up to 2^32 blocks. The maximum disk size is 4KiB *2^32 = 16TB (remember 2^10 = 1024). A disk block can store 4KiB / 4B (each pointer needs to be 32 bits) = 1024 pointers. Each pointer refers to a 4KiB disk block - so you can refer up to 1024*4KiB = 4MiB of data. For the same disk configuration, a double indirect block stores 1024 pointers to 1024 indirection tables. Thus a double-indirect block can refer up to 1024 * 4MiB = 4GB of data. Similarly, a triple indirect block can refer up to 4TB of data. Naturally though, this is three times as slow.

A directory is just a mapping of names to inode numbers. It’s typically just a normal file, but with some special bits set in its inode and a very specific structure for its contents. POSIX provides a small set of functions to read the filename and inode number for each entry, which we will talk about in depth later in this chapter.

Let’s think about what it looks like in the actual file system. Theoretically, directories are just like actual files. The disk blocks will contain directory entries or dirents. What that means is that our disk block can look like this

| inode_num | name | | ----------- | ------ |

| 2043567 | hi.txt | | ... |

Each directory entry could either be a fixed size, or a variable

c-string. It depends on how the particular filesystem implements it at

the lower level. To see a mapping of filenames to inode numbers on a

POSIX system, from a shell, use ls with the -i option

# ls -i

12983989 dirlist.c 12984068 sandwich.c

In standard unix file systems the following entries are specially added on requests to read a directory.

-

.represents the current directory -

..represents the parent directory -

Note that ... is NOT a valid representation of any directory (this not

the grandparent directory). It could however be the name of a file on

disk. Though confusingly, zsh provides this as a handy shortcut to the

grandparent directory should it exist.

Additional facts about name-related conventions:

-

Files that start with ’.’ on disk are conventionally considered ’hidden’ and will not be listed by programs like

lswithout additional flags (-a). This is not a feature of the filesystem and programs may choose to ignore this. -

Some files may also start with a null byte. These are usually abstract unix sockets and are used to prevent cluttering up the filesystem since they will be effectively hidden by any program not expecting them. They will, however, be listed by tools that detail information about sockets, so this is not a feature providing security.

While interacting with a file in C is done by using open to open the

file and then read or write to interact with the file before calling

close to release resources, directories have special calls such as,

opendir, closedir and readdir. There is no function writedir

since typically that implies creating a file or link.

To explore these functions, let’s write a program to search the contents of a directory for a particular file. (The code below has a bug, try to spot it!)

int exists(char *directory, char *name) {

struct dirent *dp;

DIR *dirp = opendir(directory);

while ((dp = readdir(dirp)) != NULL) {

puts(dp->d_name);

if (!strcmp(dp->d_name, name)) {

return 1; /* Found */

}

}

closedir(dirp);

return 0; /* Not Found */

}The above code has a subtle bug: It leaks resources! If a matching

filename is found then ‘closedir’ is never called as part of the early

return. Any file descriptors opened, and any memory allocated, by

opendir are never released. This means eventually the process will run

out of resources and an open or opendir call will fail.

The fix is to ensure we free up resources in every possible code-path.

In the above code this means calling closedir before return 1.

Forgetting to release resources is a common C programming bug because

there is no support in the C lanaguage to ensure resources are always

released with all codepaths.

Note: after a call to fork(), either (XOR) the parent or the child can use readdir(), rewinddir() or seekdir(). If both the parent and the child use the above, behavior is undefined.

There are two main gotchas and one consideration: The readdir function

returns “.” (current directory) and “..” (parent directory). If you are

looking for sub-directories, you need to explicitly exclude these

directories.

For many applications it’s reasonable to check the current directory first before recursively searching sub-directories. This can be achieved by storing the results in a linked list, or resetting the directory struct to restart from the beginning.

The following code attempts to list all files in a directory recursively. As an exercise, try to identify the bugs it introduces.

void dirlist(char *path) {

struct dirent *dp;

DIR *dirp = opendir(path);

while ((dp = readdir(dirp)) != NULL) {

char newpath[strlen(path) + strlen(dp->d_name) + 1];

sprintf(newpath,"%s/%s", newpath, dp->d_name);

printf("%s\n", dp->d_name);

dirlist(newpath);

}

}

int main(int argc, char **argv) { dirlist(argv[1]); return 0; }Did you find all 5 bugs?

// Check opendir result (perhaps user gave us a path that can not be opened as a directory

if (!dirp) { perror("Could not open directory"); return; }

// +2 as we need space for the / and the terminating 0

char newpath[strlen(path) + strlen(dp->d_name) + 2];

// Correct parameter

sprintf(newpath,"%s/%s", path, dp->d_name);

// Perform stat test (and verify) before recursing

if (0 == stat(newpath,&s) && S_ISDIR(s.st_mode)) dirlist(newpath)

// Resource leak: the directory file handle is not closed after the while loop

closedir(dirp);One final note of caution: readdir is not thread-safe! You shouldn’t

use the re-entrant version of the function. Synchronizing the filesytem

within a process is important, so use locks around readdir

See the man page of readdir for more details.

Links are what force us to model a filesystem as a tree rather than a graph. While modelling the filesystem as a tree would imply that every inode has a unique parent directory, links allow inodes to present themselves as files in multiple places, potentially with different names, thus leading to an inode having multiple parents directories.

The first kind of link is a hard link. A hard link is simply an entry in a directory assigning some name to an inode number that already has a different name and mapping in either the same directory or a different one. If we already have a file on a file system we can create another link to the same inode using the ‘ln’ command:

$ ln file1.txt blip.txt

However blip.txt is the same file; if I edit blip I’m editing the same file as ‘file1.txt!’ We can prove this by showing that both file names refer to the same inode:

$ ls -i file1.txt blip.txt

134235 file1.txt

134235 blip.txt

The equivalent C call is link

// Function Prototype

int link(const char *path1, const char *path2);

link("file1.txt", "blip.txt");For simplicity the above examples made hard links inside the same directory. Hard links can be created anywhere inside the same filesystem.

The second kind of link is a soft link - or a symbolic link or a symlink. A symbolic link is different because it does not deal with inode numbers directly. Instead a symbolic link is a regular file with a special bit set and stores a path to another file. Quite simply, without the special bit, it is nothing more than a text file with a file path inside. Note that when people generally talk about a link without specifying hard or soft, they are referring to a hard link.

To create a symbolic link in the shell use ln -s. To read the contents

of the link as just a file use readlink. These are both demonstrated

below:

$ ln -s file1.txt file2.txt

$ ls -i file1.txt blip.txt

134235 file1.txt

134236 file2.txt

134235 blip.txt

$ cat file1.txt

file1!

$ cat file2.txt

file1!

$ cat blip.txt

file1!

$ echo edited file2 >> file2.txt # >> is bash syntax for append to file

$ cat file1.txt

file1!

edited file2

$ cat file2.txt

I'm file1!

edited file2

$ cat blip.txt

file1!

edited file2

$ readlink myfile.txt

file2.txt

Note that file2.txt and file1.txt have different inode numbers,

unlike the hard link, blip.txt.

There is a C library call to create symlinks which is similar to link:

symlink(const char *target, const char *symlink);Some advantages of symbolic links are

-

Can refer to files that don’t exist yet

-

Unlike hard links, can refer to directories as well as regular files

-

Can refer to files (and directories) that exist outside of the current file system

However, symlinks have a key disadvantage, they as slower than regular

files and directories. When the links contents are read, they must be

interpreted as a new path to the target file, resulting in an additional

call to open and read since the real file must be opened and read.

Another disadvantage is that POSIX will not let you hard link

directories whereas soft links are allowed. The ln command will only

allow root to do this and only if you provide the -d option. However

even root may not be able to perform this because most filesystems

prevent it!

The integrity of the file system assumes the directory structure (excluding softlinks which we will talk about later) is a non-cyclic tree that is reachable from the root directory. It becomes expensive to enforce or verify this constraint if directory linking is allowed. Breaking these assumptions can cause file integrity tools to not be able to repair the file system. Recursive searches potentially never terminate and directories can have more than one parent but “..” can only refer to a single parent. All in all, a bad idea.

When you remove a file (using rm or unlink) you are removing an

inode reference from a directory. However the inode may still be

referenced from other directories. In order to determine if the contents

of the file are still required, each inode keeps a reference count that

is updated whenever a new link is created or destroyed. This count only

tracks hard links, symlinks are allowed to refer to a non-existent file

and thus, do not matter.

An example use of hard-links is to efficiently create multiple archives of a file system at different points in time. Once the archive area has a copy of a particular file, then future archives can re-use these archive files rather than creating a duplicate file. Apple’s “Time Machine” software does this.

Now that we have definitions talk about directories, we come across the

concept of a path. A path is a sequence of directories that provide one

with a "path" in the filesystem graph. However, there are some nuances.

It is possible to have a path called a/b/../c/./. Since .. and .

are special entries in directories, this is a valid path that actually

refers to a/c. Most filesystem functions will allow uncompressed paths

to be passed in. The C library provides a function realpath to

compress the path or get the realpath. To simplify by hand remember that

.. means ‘parent folder’ and that . means ‘current folder’. Below is

an example that illustrates the simplification of the a/b/../c/. by

using cd in a shell to navigate a filesystem.

-

cd a(in a) -

cd b(in a/b) -

cd ..(in a, because .. represents ‘parent folder’) -

cd c(in a/c) -

cd .(in a/c, because . represents ‘current folder’)

Thus, this path can be simplified to a/c.

How can we distinguish between a regular file and a directory? For that matter there’s many other attributes that files also might contain. You may know that on most UNIX systems, unlike windows systems, a file’s type is not determined by its extension. How does the system know what type the file is?

All of this information is stored within an inode. To access it, use the stat calls. For example, to find out when my ‘notes.txt’ file was last accessed.

struct stat s;

stat("notes.txt", &s);

printf("Last accessed %s", ctime(&s.st_atime));There are actually three versions of stat;

int stat(const char *path, struct stat *buf);

int fstat(int fd, struct stat *buf);

int lstat(const char *path, struct stat *buf);For example, you can use fstat to find out the meta-information about

a file if you already have an file descriptor associated with that file

FILE *file = fopen("notes.txt", "r");

int fd = fileno(file); /* Just for fun - extract the file descriptor from a C FILE struct */

struct stat s;

fstat(fd, & s);

printf("Last accessed %s", ctime(&s.st_atime));lstat is almost the same as stat but handles symbolic links

differently. From the stat man page:

lstat() is identical to stat(), except that if pathname is a symbolic link, then it returns information about the link itself, not the file that it refers to.

The stat functions make use of struct stat. From the stat man page:

struct stat {

dev_t st_dev; /* ID of device containing file */

ino_t st_ino; /* Inode number */

mode_t st_mode; /* File type and mode */

nlink_t st_nlink; /* Number of hard links */

uid_t st_uid; /* User ID of owner */

gid_t st_gid; /* Group ID of owner */

dev_t st_rdev; /* Device ID (if special file) */

off_t st_size; /* Total size, in bytes */

blksize_t st_blksize; /* Block size for filesystem I/O */

blkcnt_t st_blocks; /* Number of 512B blocks allocated */

struct timespec st_atim; /* Time of last access */

struct timespec st_mtim; /* Time of last modification */

struct timespec st_ctim; /* Time of last status change */

};The st_mode field can be used to distinguish between regular files and

directories. To accomplish this, you will also need the macros,

S_ISDIR and S_ISREG.

struct stat s;

if (0 == stat(name, &s)) {

printf("%s ", name);

if (S_ISDIR( s.st_mode)) puts("is a directory");

if (S_ISREG( s.st_mode)) puts("is a regular file");

} else {

perror("stat failed - are you sure I can read this file's meta data?");

}Permissions are a key part of the way UNIX systems provide security in a

filesystem. You may have noticed that the st_mode field in struct stat contains more than just the file type. It also contains the mode,

a description detailing what a user can and can’t do with a given file.

There are usually three sets of permissions for any file. Permissions

for the user, the group and other. For each of the three

categories we need to keep track of whether or not the user is allowed

to read the file, write to the file, and execute the file. Since there

are three categories and three permissions, permissions are usually

represented as a 3-digit octal number. For each digit the least

significant byte corresponds to read privileges, the middle one to write

privileges and the final byte to execute privileges. They are always

presented as User, Group, Other (UGO). Below are some common

examples:

-

755:

rwx r-x r-xuser:

rwx, group:r-x, others:r-xUser can read, write and execute. Group and others can only read and execute.

-

644:

rw- r– r–user:

rw-, group:r–, others:r–User can read and write. Group and others can only read.

It is worth noting that the rwx bits for a directory have slightly

different meaning. Write-access to a directory will allow you to create

or delete new files or directories inside (you can think about this as

just having write access to the dirent mappings). Read-access to a

directory will allow you to list a directory’s contents (this is just

read access to the dirent mapping). Execute will allow you to enter the

directory and access it. Without the execute bit it is not possible to

create or remove files or directories since you cannot access them. You

can, however, list the contents of the directory.

There are several command line utilities for interacting with a file’s

mode. mknod changes the type of the file. chmod takes a number and a

file and changes the permission bits. However, before we can discuss

chmod in detail, we must also understand the user id (uid) and group

id (gid) as well.

Every user in a UNIX system has a user id. This is a unique number that

can identify a user. Similarly, users can be added to collections called

groups, and every group also has a uniquely identifying number. Groups

have a variety of uses on UNIX systems. They can be assigned

capabilities - a way of describing the level of control a user has over

a system. For example, a group you may have run into is the sudoers

group, a set of trusted users who are allowed to use the command sudo

to temporarily gain higher privileges. (We’ll talk more about how sudo

works in this chapter). Every file, upon creation, an owner, the creator

of the file. This owner’s user id (uid) can be found inside the

st_mode file of a struct stat with a call to stat. Similarly the

group id (gid) is set as well.

Every process can determine it’s uid and gid with getuid and

getgid. When a processes tries to open a file with a specific mode,

it’s uid and gid are compared with the uid and gid of the

file. If the uids match, then the process’s request to open the file

will be compared with the bits on the user field of the file’s

permissions. Similarly, if the gids match, then the process’s request

will be compared with the group field of the permissions. Finally, if

none of the ids match, then the other field will apply.

Before we discuss how to change permission bits, we should be able to

read them. In C, the stat family of library calls can be used. To read

permission bits from the command line, use ‘ls -l’. Note that the

permissions will outputed in the format ‘drwxrwxrwx’. The first

character indicates the type of file type. Possible values for the first

character:

-

(-) regular file

-

(d) directory

-

(c) character device file

-

(l) symbolic link

-

(p) pipe

-

(b) block device

-

(s) socket

Alternatively, use the program stat which presents all the information

that one could retrieve from the stat library call.

To change the permission bits, there is a system call, int chmod(const char *path, mode_t mode);. In order to simplify our examples, we will

be using the command line utility of the same name chmod (short of

“change mode”). There are two common ways to use chmod ; either with

an octal value or with a symbolic string:

$ chmod 644 file1

$ chmod 755 file2

$ chmod 700 file3

$ chmod ugo-w file4

$ chmod o-rx file4

The base-8 (‘octal’) digits describe the permissions for each role: The user who owns the file, the group and everyone else. The octal number is the sum of three values given to the three types of permission: read(4), write(2), execute(1)

Example: chmod 755 myfile

-

r + w + x = digit * user has 4+2+1, full permission

-

group has 4+0+1, read and execute permission

-

all users have 4+0+1, read and execute permission

The umask subtracts (reduces) permission bits from 777 and is used

when new files and new directories are created by open, mkdir etc. By

default the umask is set to 022 (octal), which means that group and

other privileges will not include the writable bit . Each process

(including the shell) has a current umask value. When forking, the child

inherits the parent’s umask value.

For example, by setting the umask to 077 in the shell, ensures that

future file and directory creation will only be accessible to the

current user,

$ umask 077

$ mkdir secretdir

As a code example, suppose a new file is created with open() and mode

bits 666 (write and read bits for user,group and

other):

open("myfile", O_CREAT, S_IRUSR | S_IWUSR | S_IRGRP | S_IWGRP | S_IROTH | S_IWOTH);If umask is octal 022, then the permissions of the created file will

be 0666 & ~022 ie.

S_IRUSR | S_IWUSR | S_IRGRP | S_IROTHYou may have noticed an additional bit that files with execute

permission may have set. This bit is the setuid bit. It indicated that

when run, the program with set the uid of the user to that of the owner

of the file. Similar, there is a setgid bit which sets the gid of the

executor to the gid of the owner. The canonical example of a program

with setuid set is sudo.

sudo is usually a program that is owned by the root user - a user that

has all capabilities. By using sudo an otherwise unprivileged user can

gain access to most parts of the system. This is useful for running

programs that may require elevated privileges, such as using chown to

change ownership of a file, or to use mount to mount or unmount

filesystems (an action we will discuss later in this chapter). Here are

some examples:

$ sudo mount /dev/sda2 /stuff/mydisk

$ sudo adduser fred

$ ls -l /usr/bin/sudo

-r-s--x--x 1 root wheel 327920 Oct 24 09:04 /usr/bin/sudo

When executing a process with the setuid bit, it is still possible to

determine a user’s original uid with getuid. The real action of the

setuid bit is to set the effective userid (euid) which can be

determined with geteuid. The actions of getuid and geteuid are

described below.

-

getuidreturns the real user id (zero if logged in as root) -

geteuidreturns the effective userid (zero if acting as root, e.g. due to the setuid flag set on a program)

These functions can allow one to write a program that can only be run by

a privileged user by checking geteuid or go a step further and ensure

that the only user who can run the code is root by using getuid.

Sticky bits as we use them today do not serve the same purpose as their initial introduction. Sticky bits were a bit that could be set on an executable file that would allow a program’s text segment to remain in swap even after the end of the program’s execution. This made subsequent executions of the same program faster. Today, this behavior is no longer supported and the sticky bit only holds meaning when set on a directory,

When a directory’s sticky bit is set only the file’s owner, the

directory’s owner, and the root user can rename or delete the file. This

is useful when multiple users have write access to a common directory. A

common use of the sticky bit is for the shared and writable /tmp

directory.

To set the sticky bit, use chmod +t.

aneesh$ mkdir sticky

aneesh$ chmod +t sticky

aneesh$ ls -l

drwxr-xr-x 7 aneesh aneesh 4096 Nov 1 14:19 .

drwxr-xr-x 53 aneesh aneesh 4096 Nov 1 14:19 ..

drwxr-xr-t 2 aneesh aneesh 4096 Nov 1 14:19 sticky

aneesh$ su newuser

newuser$ rm -rf sticky

rm: cannot remove 'sticky': Permission denied

newuser$ exit

aneesh$ rm -rf sticky

aneesh$ ls -l

drwxr-xr-x 7 aneesh aneesh 4096 Nov 1 14:19 .

drwxr-xr-x 53 aneesh aneesh 4096 Nov 1 14:19 ..

Note that in the example above, the username is prepended to the prompt,

and the command su is used to switch users.

POSIX systems, such as Linux and Mac OSX (which is based on BSD) include several virtual filesystems that are mounted (available) as part of the file-system. Files inside these virtual filesystems do not exist on the disk; they are generated dynamically by the kernel when a process requests a directory listing. Linux provides 3 main virtual filesystems

/dev - A list of physical and virtual devices (for example network card, cdrom, random number generator)

/proc - A list of resources used by each process and (by tradition) set of system information

/sys - An organized list of internal kernel entities

For example if I want a continuous stream of 0s, I can cat /dev/zero.

Another example is the file /dev/null - a great place to store bits

that you never need to read! Bytes sent to /dev/null/ are never

stored - they are simply discarded. A common use of /dev/null is to

discard standard output. For example,

$ ls . >/dev/null

Given the multitude of operations that are available to you from the filesystem, let’s explore some tools and techniques that can be used to manage files and filesystems.

One example is creating a secure directory. Suppose you created your own directory in /tmp and then set the permissions so that only you can use the directory (see below). Is this secure?

$ mkdir /tmp/mystuff

$ chmod 700 /tmp/mystuff

There is a window of opportunity between when the directory is created and when it’s permissions are changed. This leads to several vulnerabilities that are based on a race condition.

Another user replaces mystuff with a hard link to an existing file or

directory owned by the second user, then they would be able to read and

control the contents of the mystuff directory. Oh no - our secrets are

no longer secret!

However in this specific example the /tmp directory has the sticky bit

set, so other users may not delete the mystuff directory, and the

simple attack scenario described above is impossible. This does not mean

that creating the directory and then later making the directory private

is secure! A better version is to atomically create the directory with

the correct permissions from its inception -

$ mkdir -m 700 /tmp/mystuff

/dev/random is a file which contains number generator where the

entropy is determined from environmental noise. Random will block/wait

until enough entropy is collected from the environment.

/dev/urandom is like random, but differs in the fact that it allows

for repetition (lower entropy threshold), thus wont block.

Use the versatile dd command. For example, the following command

copies 1 MiB of data from the file /dev/urandom to the file

/dev/null. The data is copied as 1024 blocks of blocksize 1024 bytes.

$ dd if=/dev/urandom of=/dev/null bs=1k count=1024

Both the input and output files in the example above are virtual - they don’t exist on a disk. This means the speed of the transfer is unaffected by hardware power.

dd is also commonly used to make a copy of a disk or an entire

filesystem to create images that can either be burned on to other disks

or to distribute data to other users.

The touch executable creates file if it does not exist and also

updates the file’s last modified time to be the current time. For

example, we can make a new private file with the current

time:

$ umask 077 # all future new files will maskout all r,w,x bits for group and other access

$ touch file123 # create a file if it does not exist, and update its modified time

$ stat file123

File: `file123'

Size: 0 Blocks: 0 IO Block: 65536 regular empty file

Device: 21h/33d Inode: 226148 Links: 1

Access: (0600/-rw-------) Uid: (395606/ angrave) Gid: (61019/ ews)

Access: 2014-11-12 13:42:06.000000000 -0600

Modify: 2014-11-12 13:42:06.001787000 -0600

Change: 2014-11-12 13:42:06.001787000 -0600

An example use of touch is to force make to recompile a file that is unchanged after modifying the compiler options inside the makefile. Remember that make is ‘lazy’ - it will compare the modified time of the source file with the corresponding output file to see if the file needs to be recompiled

$ touch myprogram.c # force my source file to be recompiled

$ make

To manage filesystems on your machine, use mount. Using mount without

any options generates a list (one filesystem per line) of mounted

filesystems including networked, virtual and local (spinning disk /

SSD-based) filesystems. Here is a typical output of mount

$ mount

/dev/mapper/cs241--server_sys-root on / type ext4 (rw)

proc on /proc type proc (rw)

sysfs on /sys type sysfs (rw)

devpts on /dev/pts type devpts (rw,gid=5,mode=620)

tmpfs on /dev/shm type tmpfs (rw,rootcontext="system_u:object_r:tmpfs_t:s0")

/dev/sda1 on /boot type ext3 (rw)

/dev/mapper/cs241--server_sys-srv on /srv type ext4 (rw)

/dev/mapper/cs241--server_sys-tmp on /tmp type ext4 (rw)

/dev/mapper/cs241--server_sys-var on /var type ext4 (rw)rw,bind)

/srv/software/Mathematica-8.0 on /software/Mathematica-8.0 type none (rw,bind)

engr-ews-homes.engr.illinois.edu:/fs1-homes/angrave/linux on /home/angrave type nfs (rw,soft,intr,tcp,noacl,acregmin=30,vers=3,sec=sys,sloppy,addr=128.174.252.102)

Notice that each line includes the filesystem type source of the

filesystem and mount point. To reduce this output we can pipe it into

grep and only see lines that match a regular expression.

>mount | grep proc # only see lines that contain 'proc'

proc on /proc type proc (rw)

none on /proc/sys/fs/binfmt_misc type binfmt_misc (rw)

Suppose you had downloaded a bootable linux disk image from the http://cosmos.cites.illinois.edu/pub/archlinux/iso/2015.04.01/archlinux-2015.04.01-dual.iso

wget $URL

Before putting the filesystem on a CD, we can mount the file as a filesystem and explore its contents. Note, mount requires root access, so let’s run it using sudo

$ mkdir arch

$ sudo mount -o loop archlinux-2015.04.01-dual.iso ./arch

$ cd arch

Before the mount command, the arch directory is new and obviously empty.

After mounting, the contents of arch/ will be drawn from the files and

directories stored in the filesystem stored inside the

archlinux-2014.11.01-dual.iso file. The loop option is required

because we want to mount a regular file not a block device such as a

physical disk.

The loop option wraps the original file as a block device - in this

example we will find out below that the file system is provided under

/dev/loop0 : We can check the filesystem type and mount options by

running the mount command without any parameters. We will pipe the

output into grep so that we only see the relevant output line(s) that

contain ‘arch’

$ mount | grep arch

/home/demo/archlinux-2014.11.01-dual.iso on /home/demo/arch type iso9660 (rw,loop=/dev/loop0)

The iso9660 filesystem is a read-only filesystem originally designed for optical storage media (i.e. CDRoms). Attempting to change the contents of the filesystem will fail

$ touch arch/nocando

touch: cannot touch `/home/demo/arch/nocando': Read-only file system

While we traditionally think of reading and writing from a file as

operation that happen by using the read and write calls, there is an

alternative, mapping a file into memory using mmap. mmap can also be

used for IPC, and you can see more about mmap as a system call that

enables shared memory in the IPC chapter. In this chapter, we’ll briefly

explore mmap as a filesystem operation.

mmap takes a file and maps its contents into memory. This allows a

user to treat the entire file as a buffer in memory for easier semantics

while programming, and to avoid having to read a file as discrete chunks

explicitly.

Not all filesystems support using mmap for IO, but amongst those that

do, not all have the same behavior. Some will simply implement mmap as

a wrapper around read and write. Others will add additional

optimizations by taking advantage of the kernel’s page cache. Of course,

such optimization can be used in the implementation of read and

write as well, so often using mmap does not impact performance.

mmap is used to perform some operations such as loading libraries and

processes into memory. If many programs only need read-access to the

same file (e.g. /bin/bash, the C library) then the same physical

memory can be shared between multiple processes.

The process to map a file into memory is simple:

-

mmaprequires a file descriptor, so we need toopenthe file first -

We seek to our desired size and write one byte to ensure that the file is sufficient length

-

When finished call munmap to unmap the file from memory.

Here is a quick example.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <sys/mman.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <errno.h>

#include <string.h>

int fail(char *filename, int linenumber) {

fprintf(stderr, "%s:%d %s\n", filename, linenumber, strerror(errno));

exit(1);

return 0; /*Make compiler happy */

}

#define QUIT fail(__FILE__, __LINE__ )

int main() {

// We want a file big enough to hold 10 integers

int size = sizeof(int) * 10;

int fd = open("data", O_RDWR | O_CREAT | O_TRUNC, 0600); //6 = read+write for me!

lseek(fd, size, SEEK_SET);

write(fd, "A", 1);

void *addr = mmap(0, size, PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE, MAP_SHARED, fd, 0);

printf("Mapped at %p\n", addr);

if (addr == (void*) -1 ) QUIT;

int *array = addr;

array[0] = 0x12345678;

array[1] = 0xdeadc0de;

munmap(addr,size);

return 0;

}The careful reader may notice that our integers were written in

least-significant-byte format (because that is the endianness of the

CPU) and that we allocated a file that is one byte too many! The

PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE options specify the virtual memory protection.

The option PROT_EXEC (not used here) can be set to allow CPU execution

of instructions in memory (e.g. this would be useful if you mapped an

executable or library).

Most filesystems cache significant amounts of disk data in physical memory. Linux, in this respect, is particularly extreme: All unused memory is used as a giant disk cache. The disk cache can have significant impact on overall system performance because disk I/O is slow. This is especially true for random access requests on spinning disks where the disk read-write latency is dominated by the seek time required to move the read-write disk head to the correct position.

For efficiency, the kernel caches recently used disk blocks. For writing, we have to choose a trade-off between performance and reliability: Disk writes can also be cached (“Write-back cache”) where modified disk blocks are stored in memory until evicted. Alternatively a ‘write-through cache’ policy can be employed where disk writes are sent immediately to the disk. The latter is safer (as filesystem modifications are quickly stored to persistent media) but slower than a write-back cache; If writes are cached then they can be delayed and efficiently scheduled based on the physical position of each disk block. Note this is a simplified description because solid state drives (SSDs) can be used as a secondary write-back cache.

Both solid state disks (SSD) and spinning disks have improved performance when reading or writing sequential data. Thus operating system can often use a read-ahead strategy to amortize the read-request costs (e.g. time cost for a spinning disk) and request several contiguous disk blocks per request. By issuing an I/O request for the next disk block before the user application requires the next disk block, the apparent disk I/O latency can be reduced.

If your data is important and needs to be force written to disk, call

sync to request that a filesystem changes be written (flushed) to

disk. However, not all operating systems honor this request and even if

the data is evicted from the kernel buffers the disk firmware use an

internal on-disk cache or may not yet have finished changing the

physical media. Note you can also request that all changes associated

with a particular file descriptor are flushed to disk using fsync(int fd)

If your operating system fails in the middle of an operation, most modern file systems do something called journalling that work around this. What the file system does is before it completes a potentially expensive operation, is that it writes what it is going to do down in a journal. In the case of a crash or failure, one can step through the journal and see which files are corrupt and fix them. This is a way to salvage hard disks in cases there is critical data and there is no apparent backup.

Even though it is unlikely for your computer, programming for data centers means that disks fail every few seconds. Disk failures are measured using “Mean-Time-Failure”. For large arrays, the mean failure time can be surprisingly short. For example if the MTTF(single disk) = 30,000 hours, then the MTTF(1000 disks)= 30000/1000=30 hours or about a day and a half!

One way to protect against this is to store the data twice! This is the main principle of a “RAID-1” disk array. RAID is short for redundant array of inexpensive disks. By duplicating the writes to a disk with writes to another backup disk, there are exactly two copies of the data. If one disk fails, the other disk serves as the only copy until it can be re-cloned. Reading data is faster since data can be requested from either disk, but writes are potentially twice as slow because now two write commands need to be issued for every disk block write. Compared to using a single disk, the cost of storage per byte has doubled.

Another common RAID scheme is RAID-0, meaning that a file could be split up among two disks, but if any one of the disks fail then the files are irrecoverable. This has the benefit of halving write times because one part of the file could be writing to hard disk one and another part to hard disk two.

It is also common to combine these systems. If you have a lot of hard disks, consider RAID-10. This is where you have two systems of RAID-1, but the systems are hooked up in RAID-0 to each other. This means you would get roughly the same speed from the slowdowns but now any one disk can fail and you can recover that disk. If two disks from opposing raid partitions fail there is a chance that recover can happen though we don’t could on it most of the time.

RAID-3 uses parity codes instead of mirroring the data. For each N-bits written we will write one extra bit, the ‘Parity bit’ that ensures the total number of 1s written is even. The parity bit is written to an additional disk. If any one disk (including the parity disk) is lost, then its contents can still be computed using the contents of the other disks.

One disadvantage of RAID-3 is that whenever a disk block is written, the parity block will always be written too. This means that there is effectively a bottleneck in a separate disk. In practice, this is more likely to cause a failure because one disk is being used 100% of the time and once that disk fails then the other disks are more prone to failure.

A single disk failure will not result in data loss (because there is sufficient data to rebuild the array from the remaining disks). Data-loss will occur when a two disks are unusable because there is no longer sufficient data to rebuild the array. We can calculate the probability of a two disk failure based on the repair time which includes not just the time to insert a new disk but the time required to rebuild the entire contents of the array.

MTTF = mean time to failure

MTTR = mean time to repair

N = number of original disks

p = MTTR / (MTTF-one-disk / (N-1))

Using typical numbers (MTTR=1day, MTTF=1000days, N-1 = 9, p=0.009)

There is a 1% chance that another drive will fail during the rebuild process (at that point you had better hope you still have an accessible backup of your original data. In practice the probability of a second failure during the repair process is likely higher because rebuilding the array is I/O-intensive (and on top of normal I/O request activity). This higher I/O load will also stress the disk array

RAID-5 is similar to RAID-3 except that the check block (parity information) is assigned to different disks for different blocks. The check-block is ‘rotated’ through the disk array. RAID-5 provides better read and write performance than RAID-3 because there is no longer the bottleneck of the single parity disk. The one drawback is that you need more disks to have this setup and there are more complicated algorithms need to be used

Failure is the common case. Google reports 2-10% of disks fail per year Now multiply that by 60,000+ disks in a single warehouse… Must survive failure of not just a disk, but a rack of servers or a whole data center

Solutions Simple redundancy (2 or 3 copies of each file) e.g., Google GFS (2001) More efficient redundancy (analogous to RAID 3++) e.g., http://goo.gl/LwFIy (~2010): customizable replication including Reed-Solomon codes with 1.5x redundancy

Software developers need to implement filesystems all the time. Don’t believe me? Take a look at Hadoop, GlusterFS, Qumulo, etc. Filesystems are hot areas of research now because people have realized that the software models that we devised don’t take full advantage of our current hardware. Additionally, the hardware that we use for storing information is getting better and better all the time. As such, you may end up designing a filesystem yourself someday. In this section we will go over one of our fake filesystems that we talk about in class and “walk through” some examples of how things work.

So what does our hypothetical filesystem look like? We will base it off of the , a very simple filesystem that happens to be the first filesystem that Linux ran on. Laid out sequentially on disk, we first have our superblock. The superblock stores important metadata about the entire filesystem. Since we want to be able to read this block before we know anything else about the data on disk, this needs to be in a well-known location so the very start of the disk is a good choice. After the superblock, we’ll keep a map of which inodes are being used. The n’th bit is set if the n’th inode – $$ 0 $$ being the inode root – is being used. Similarly, we store a map recording which datablocks are used. Finally, we have an array of inodes followed by the rest of the disk - implicitly partitioned into datablocks. It’s important to note that there may not be any real distinction from one datablock to the next from the perspective of the hardware components of the disk. Thinking about the disk as an array of datablocks is simply something we do so that we have a way to describe where files live on disk.

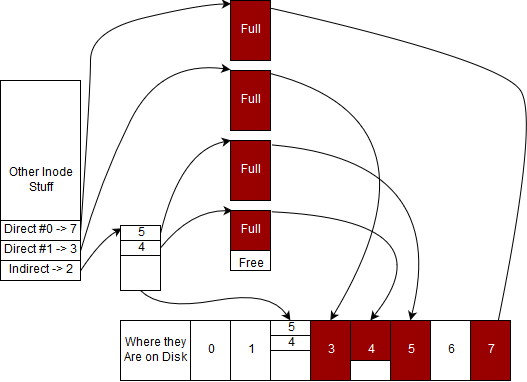

Below, we have an example of how an inode that describes a file may look. Note that for the sake of simplicity, we have drawn arrows mapping datablock numbers in the inode to their locations on disk, these aren’t pointers so much as indicies into an array.

We will assume that a data block is 4 KiB.

Note that a file will fill up each of its data blocks completely before requesting an additional data block. We will refer to this property as as the file being compact. The file presented above is interesting since it uses all of it’s direct blocks, one of the entries for it’s indirect block and partially uses another indirect block.

The following subsections will all refer to the file presented above.

The size of a file is not something that we can compute by staring at it. We need additional information that is typically stored in the inode. This is because the filesystem isn’t aware of the actual contents of what is in a file. That data is considered the user’s. However, we can compute an upper bound by looking at how many blocks the file uses.

There are two full direct blocks, which together store $$ 2sizeof(data_block)=24KiB=8KiB $$.

There are two used blocks referenced by the indirect block, which can store up to $$ 8KiB $$ as calculated above.

We can now add these values to get an upper bound on the file size of $$ 16KiB $$.

What about a lower bound? We know that we must use the two direct blocks, one block referenced by the indirect block and at least 1 byte of a second block referenced by the indirect block. With this information, we can work out the lower bound to be $$ 2*4KiB+4KiB+1=12KiB+1B $$.

Note that our calculations so far have been to determine how much data the user is storing on disk. We have not considered the overhead of storing this data incurred while using this filesystem. You’ll notice that we use an indirect block to store the disk block numbers of blocks used beyond the two direct blocks. While doing our above calculations, we did not take this block into account while computing the filesize. This would instead be counted as the overhead of the file, and thus the total overhead of storing this file on disk is $$ sizeof(indirect_block)=4KiB) $$.

Performing reads tend to be pretty easy in our filesystem because our files are compact. Let’s say that we want to read the entirety of this particular file. What we’d start by doing is go to the inode’s direct struct and find the first direct inode number. In our case it is #7. Then we find the 7th data block from the start of all data blocks. Then we read all of those bytes. We do the same thing for all of the direct nodes. What do we do after? We go to the indirect block and read the indirect block. We know that every 4 bytes of the indirect block are either a sentinel node (-1) or the number of another data block. In our particular example, the first four bytes evaluate to the integer 5, meaning that our data continues on the 5th datablock from the beginning. We do the same for data block #4 and we stop after because we exceed the size of the inode

Now, let’s think about the edge cases. How would you start the read starting at an arbitrary offset of $$ n $$ bytes given that block sizes are $$ 4 KiBs $$. How many indirect blocks should there be if the filesystem is correct (hint: think about using the size of the inode)

Performing writes fall into two categories, writes to files and writes

to directories. First we’ll focus on files and assume that we are

writing a byte to the $$ 6

Some questions for you. How would you consider performing a write that would go across data block boundaries? How would you consider performing a write whose write after adding the offset would extend the length of the file? How would you consider performing a write where the offset is greater than the length of the original file?

Performing a write to a directory meaning that an inode needs to be added to a directory. If we pretend that the example above is a directory. We know that we will be adding at most one directory entry at a time. Meaning that we have to have enough space for one directory entry in our datablocks. Luckily the last data block that we have has enough free space. This means we just need to find the number of the last data block as we did above, go to where the data ends, and write one directory entry. Don’t forget to update the size of the directory so that the next creation doesn’t overwrite your file!

Some more questions. How would you consider performing a write when the last data block is already full? How about when all the direct blocks have just been filled up and the inode doesn’t have an indirect block? What about when the first indirect entry (#4) is full? These are all edge cases you have to think about for a filesystem that really get you

Although this isn’t part of the lab originally. If you were to ask what happens when a file gets deleted, it’s actually pretty simple. If the inode is a file, then remove the directory entry in the parent directory by marking it as invalid (maybe making it point to inode -1) and skip it in your reads. You need to make sure to decrease the hard link count of the inode and if the count reaches zero, free the inode in the inode map and free all associated data blocks so they are reclaimed by the filesystem.

If the inode is a directory, first you have to recursively remove every directory entry inside After, you have to mark the directory’s inode as free and set the associated datablocks to free as well. Why don’t we have to check hardlink counts for directories? Because you can’t hard link directories! Meaning, we can just easily delete it.

-

Superblock

-

Data Block

-

Inode

-

Relative Path

-

File Metadata

-

Hard and Soft Links

-

Permission Bits

-

Mode bits

-

Working with Directories

-

Virtual File System

-

Reliable File Systems

-

RAID

-

How big can files be on a file system with 15 Direct blocks, 2 double, 3 triple indirect, 4kb blocks and 4byte entries? (Assume enough infinite blocks)

-

What is a superblock? Inode? Datablock?

-

How do I simplify

/./proc/../dev/./random/ -

In ext2, what is stored in an inode, and what is stored in a directory entry?

-

What are /sys, /proc, /dev/random, and /dev/urandom?

-

What are permission bits?

-

How do you use chmod to set user/group/owner read/write/execute permissions?

-

What does the “dd” command do?

-

What is the difference between a hard link and a symbolic link? Does the file need to exist?

-

“ls -l” shows the size of each file in a directory. Is the size stored in the directory or in the file’s inode?

Please do not edit this wiki

This content is licensed under the coursebook licensing scheme. If you find any typos. Please file an issue or make a PR. Thank you!