Wasn't this problem already solved?

Linus Torvalds needed something to manage the Linux kernel. The kernel is a massive project with thousands of contributors trying millions of experiments with a shifting hierarchy and a codebase so massive they couldn't keep it all managed on one central repository if they tried.

We're not as huge as the Linux foundation, so again: why git?

- Reality is an illusion

Git operates on the assumption that you have multiple people working on overlapping subsets of the same codebase and that, at any given moment, no two people have compatible code.

Hence, git is a distributed version control system. You have your own repository and unless you say otherwise there is no such thing as the "canonical" repository.

- Branching should be easy.

Want to try something new? Just branch. If it works - great! Merge it back into the parent. If it sucks - delete the branch and forget the whole embarrassing affair.

- You should be able to create the workflow you need.

Git is really 152 (or so) separate commands under one convenient wrapper. You can compose them any way you want to. It's the Unix Philosophy for version control.

Magic.

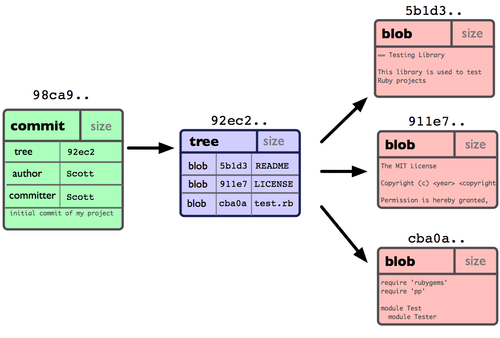

Just kidding. Inside your git repository you'll find a hidden directory named

.git. It contains a configuration file (remote repository locations, etc) and

a bunch of diffs.

That's it.

A branch is just a textfile, somewhere inside .git/ that contains a checksum

of the latest commit. Conveniently, commits are stored at these checksums. So

"switching to a branch" means "read a file, go to the set of diffs with this

checksum, apply them."

Every point in your history can be "checked out" just like a branch because

every commit you've ever made has a GUID. So you can totally

git checkout 97fb475982e6 or similar.

Unlike most version control systems, git has a staging area. You stage a

change when you git add it.

Protip: You can even stage portions of a file rather than the whole thing!

When you actually commit changes, you are really taking a diff from your current version of the file to the old version of the file. If you ever have to rollback history, git will just apply the diffs until you arrive.

cloneadd- `commit

checkoutbranchfetchmergepullpushlogstatusrebase

As discussed, git is very anarchist. So if you want to grab someone's code out of a git repository, you're not "checking it out" or being granted access: you're cloning their entire history. Then you can start adding your own history in your own little parallel universe.

Usage:

git clone https://somedomain/path/to/repo.git

git clone git://somedomain/path/to/repo.git

git clone git@somedomain:/path/to/repo.git

This stages a change to be committed. Anything you want to commit, add.

Otherwise, don't.

Usage:

git add somefile

git add ./*

This actually commits the changes in your staging area to your local repository. In git, everything in a branch is just a collection of diffs; if you apply them in the correct order, you go back through time.

You have to include a commit message. You can do so with the -m switch.

!bash

git commit -m "Some commit message"

If you don't, git will hassle you by running your default editor and make you type something and save it.

If git is already tracking some files, then you can add and commit all changes

with the -a flag:

!bash

git commit -a -m "my commit message"

In SVN, checkout means "checkout what's at the server and put it here in

front of me."

In git, it really means "switch to a different branch." The naming is perhaps unfortunate, but it does make sense: I want to check out this branch to see what is in it and make changes.

You can checkout local and remote branches.

Local:

!bash

git checkout somelocalbranch

Remote:

!bash

git fetch remotename

git checkout remotename/somebranch

We'll get to fetch in a moment. The "Remote" commands essentially brings

down server branches without modifying any of your local branches.

... but never a checkin command. What's up with that, amirite?

I almost went with a Hotel California joke; regrets.

The branch command can do several things:

- List branches:

git branch - Create a new branch:

git branch branchname - Delete a branch:

git branch -D branchname - List only remote branches:

git branch -r - List local and remote branches:

git branch -a

Create a branch and check it out at the same time:

!bash

git checkout master

git checkout -b gatlin/featureOne

vim somefile.py

git commit -a -m "finished featureOne"

git checkout master

git merge gatlin/featureone

The -b switch for checkout is pretty nifty.

We saw fetch earlier. fetch retrieves (or, in our colloquial parlance,

fetches) the state of another repository but does not change the state of

your local repository.

There is more to say about fetch. I'll leave this for a later presentation.

Usage:

git fetch remoteserver

This will look up the server you call "remoteserver" in your .git/config file

and fetch its current state. Then I can access its branches like so:

git checkout remoteserver/branchname

To merge is to take the state of another branch and merge it with the state

of the current branch.

Usage: git merge srcbranch

Think of it this way: wherever I am, if I want to bring in changes, I use

merge.

You will sometimes have conflicts. Git will fail loudly for you and tell you that you must resolve them.

For this reason merge does not automatically commit anything unless you tell

it to.

To resolve conflicts:

- Go to the files git labeled as problematic

- Make the file look like what you want it to look like

git addandgit committhose files.

If you decide it's not worth it, then git merge --abort

Here is a common workflow:

!bash

git fetch remoteserver

git checkout myownbranch

git merge remoteserver/branchname

It's so common that git has a special name for this combination: pull.

Usage:

git pull remoteserver branchname

It's just fetch and merge.

So far all the commands have been "bring me something" types of commands. I merge from your branch into my branch; I fetch from your repository into my repository, etc.

If you want a semi-centralized workflow, though (and we do), then git has a command for pushing your branch to a remote repository.

Usage:

git push remoteserver localBranchName

These are pretty simple. To see a history of your commits and commit messages:

git log

To see what is staged, unstaged, waiting to be commited, etc in your current working directory:

git status

The dreaded rebase. EVERYBODY PANIC.

Actually, don't. It's not that bad. Rebase is like merge except instead of merging in the traditional sense, it

-

undoes everything you have committed to the point that you last rebased (or branched)

-

applies changes until your branch is where the server is

-

applies your changes on top of this new foundation.

Rebase from some authoritative, more important branch down to lesser ones. So

git checkout gatlin/myfeature

git rebase dev

Not the other way around.

You can "rebase" from an earlier point in history. And, with the -i flag you

can interactively decide what to do at each stage and not just accept the

default behavior.

Go ahead and try this:

git rebase -i HEAD~3

Instead of 3, however many commits back you wish to squash. You'll see

1 pick 5e8f2d2 merge; polished fetch

2 pick 195181e pull command

3 pick 81281e9 conflict resolution on merge

4 pick ba68f7e explained branches; rebase

5 pick ed9d72f branches has its own slide; stage and commit merged

If you want to squash some together ...

1 pick 5e8f2d2 merge; polished fetch

2 squash 195181e pull command

3 squash 81281e9 conflict resolution on merge

4 squash ba68f7e explained branches; rebase

5 squash ed9d72f branches has its own slide; stage and commit merged

Revert commits a new change which undoes the old change. So it adds to your history "hey, actually, I don't like this last change."

git revert HEAD~1

This reverts the second to last commit (the ~ notation is very handy). So you

don't need to know the commit GUID.

Use the -n flag to not automatically commit this. See? The staging area is

awesome.

This actually UNDOES HISTORY!

Actually, I'm not going to tell you about this. Let's not irrevocably modify history, okay?