Up To Schedule - Back To Make Incremental Changes I - Forward To Make Incremental Changes II

Based on Lecture Materials By: Milad Fatenejad, Katy Huff, and Paul Wilson

In this lecture we shift gears slightly. The best practices of "Write Code for People" continue to be important, but we'll start to place more emphasis on the best practices of "Don't Repeat Yourself", and its twin practice of "Don't Repeat Others".

We've already seen the importance of loops as a way to avoid repeating yourself. We've also already discussed the use of functions. In this lesson, we'll explore how to use other people's modules, and how to package pieces of your code together into reusable modules.

To paste text from another application (i.e. these lecture notes) into IPython :

- select text from the website

- copy with cntl+C (or ⌘+C on Mac OSX)

- unfortunately pasting depends on your operating system and ssh program:

When in the IPython interpreter, the easiest way to paste is with the right mouse button over the window, choosing "Paste".

Click with the right mouse button over the window.

#### Mac OSX Press ⌘+V.

Click with the right mouse button over the window and then "Paste".

The code should paste and execute in IPython.

In general, for multi-line pasting, you should use the %cpaste feature of IPython.

Python has a lot of useful data type and functions built into the language, some of which you have already seen. For a full list, you can type dir(__builtins__). However, there are even more functions stored in modules. An example is the sine function, which is stored in the math module. In order to access mathematical functions, like sin, we need to import the math module. Let's take a look at a simple example:

print sin(3) # Error! Python doesn't know what sin is...yet

import math # Import the math module

math.sin(3)

print dir(math) # See a list of everything in the math module

help(math) # Get help information for the math moduleIt is not very difficult to use modules - you just have to know the module name and import it. There are a few variations on the import statement that can be used to make your life easier. Let's take a look at an example:

from math import * # import everything from math into the global namespace (A BAD IDEA IN GENERAL)

print sin(3) # notice that we don't need to type math.sin anymore

print tan(3) # the tangent function was also in math, so we can use that tooreset # Clear everything from IPython

from math import sin # Import just sin from the math module. This is a good idea.

print sin(3) # We can use sin because we just imported it

print tan(3) # Error: We only imported sin - not tanreset # Clear everything

import math as m # Same as import math, except we are renaming the module m

print m.sin(3) # This is really handy if you have module names that are longIf you intend to use python in your workflow, it is a good idea to skim the standard library documentation at the main Python documentation site, docs.python.org to get a general idea of the capabilities of python "out of the box".

Let's take a look at a nice docstring for a pandas DataFrame. Pandas is a Python data analysis toolkit, and the DataFrame is its main data type. It's equivalent to a single rectangular dataset which you'd see in many other statistical packages. For more on pandas, check out this tutorial.

import pandas

pandas.DataFrame?

Type: type

String form: <class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

File: //anaconda/lib/python2.7/site-packages/pandas/core/frame.py

Init definition: pandas.DataFrame(self, data=None, index=None, columns=None, dtype=None, copy=False)

Docstring:

Two-dimensional size-mutable, potentially heterogeneous tabular data

structure with labeled axes (rows and columns). Arithmetic operations

align on both row and column labels. Can be thought of as a dict-like

container for Series objects. The primary pandas data structure

"""

Parameters

----------

data : numpy ndarray (structured or homogeneous), dict, or DataFrame

Dict can contain Series, arrays, constants, or list-like objects

index : Index or array-like

Index to use for resulting frame. Will default to np.arange(n) if

no indexing information part of input data and no index provided

columns : Index or array-like

Column labels to use for resulting frame. Will default to

np.arange(n) if no column labels are provided

dtype : dtype, default None

Data type to force, otherwise infer

copy : boolean, default False

Copy data from inputs. Only affects DataFrame / 2d ndarray input

Examples

--------

>>> d = {'col1': ts1, 'col2': ts2}

>>> df = DataFrame(data=d, index=index)

>>> df2 = DataFrame(np.random.randn(10, 5))

>>> df3 = DataFrame(np.random.randn(10, 5),

... columns=['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e'])

See also

--------

DataFrame.from_records : constructor from tuples, also record arrays

DataFrame.from_dict : from dicts of Series, arrays, or dicts

DataFrame.from_csv : from CSV files

DataFrame.from_items : from sequence of (key, value) pairs

pandas.read_csv, pandas.read_table, pandas.read_clipboard

"""We see a nice docstring seperating into several sections. A short description of the function is given, then all the input parameters are listed, then the outputs, there are some notes and examples. Please note the docstring is longer than the code. And there are few comments in the actual code.

Short exercise: Learn about sys

Short exercise: Learn about sys

In the script we wrote to convert text files to CSV, we used the sys module. Use the IPython interpreter to learn more about the sys module and what it does. What is sys.argv and why did we only use the last n-1 elements? What is sys.stdout?

In the last lecture, we wrote code to write out some structured information in a CSV formatted file. In that case, we enclosed every element of the table in quotes. For most tools that read CSV files, this causes those elements to always be interpretted a strings. However, we had many numerical entries and may want those to be recorded as numbers.

There are three ways to do this:

- Rewrite our functions to only enclose the string elements in quotation marks for this particular data set. Straightforward, but only useful in this particular project.

- Rewrite our functions to detect which elements are really strings and which are not. Probably quite difficult and error prone.

- Find a module that does this for us already. Clearly the best choice!!!

In fact, there is a CSV module already available.

Short Exercise Use google to search for a

Short Exercise Use google to search for a python csv module.

Instead of having you learn about the CSV module from the documentation and examples, we'll point you to the most important things:

In [25]: import csv

In [26]: dir(csv)

In [27]: help(csv)

In [28]: dir(csv.DictWriter)

In [29]: csv.DictWriter?

The truth is that the documentation provided here is probably not enough to learn it by yourself. The online documentation is better, and even better are some examples that you can find online.

We'll start by adding the following to our file:

import csv

csv_writer = csv.DictWriter(sys.stdout, delimiter=',', fieldnames=column_labels)This provides a way to write CSV files from python dictionaries. More specifically:

- we will write this to the screen using

sys.stdout - we will use a comman (',') as the delimiter (Note: we can remove any reference to

csv_separatornow) - we will use

column_labelsto provide the order in which to write the fields from our data

Now we can replace the two functions we added previously:

- instead of

writeCSVHeader(column_labels,csv_separator)we havecsv_writer.writeheader() - instead of

writeCSVRow(column_labels,data_record,csv_separator)we havecsv_writer.writerow(data_record)

So that our script now ends with the following lines:

import csv

csv_writer = csv.DictWriter(sys.stdout, delimiter=',', fieldnames=column_labels)

csv_writer.writeheader()

for data_record in all_data:

csv_writer.writerow(data_record) Short Exercise: Figure out how to change the quoting behavior of the CSV writer and explore different options. Do any of them put the strings in quotations but not the numbers?

Short Exercise: Figure out how to change the quoting behavior of the CSV writer and explore different options. Do any of them put the strings in quotations but not the numbers?

Bonus Exercise: The CSV module even has a method to write multiple rows:

Bonus Exercise: The CSV module even has a method to write multiple rows: writerows(). Try using it in stead of the loop over all_data.

We still need to ensure that the numerical results in our original files are

being treated as numbers. To do so, immediately before returning our value

from extractData() we'll:

- define a list of columns that should be treated as numeric

- if we find one, convert it to a float

numeric_columns = ("Age","Income","Education","Hours per week")

if key in numeric_columns and value != "" :

value = float(value)For our set of survey data, we may now be interested in performing

some simple statistical analysis of the results. For example, we may want to

know the mean value of the Income data from all the subjects.

Since we know that taking the mean value of many numbers (and other statistics) is something we may want to do in many different projects in the future, let's make a module that contains those functions. (Note: Most of these functions are already available in existing modules and it would be best to use those, but this is a convenient example that everyone probably can understand equally well.)

Making a new module is as simple as defining functions in a new python file.

Let's call our file stats.py and start by adding a function to calculate the

mean.

def mean(vals):

"""Calculate the arithmetic mean of a list of numbers in vals"""

total = sum(vals)

length = len(vals)

return total/lengthWe can now use this module in our original script.

- Add some lines to the original script to get a list with only the

Incomedata. - Use this

mean()function to calculate the mean of those numbers.

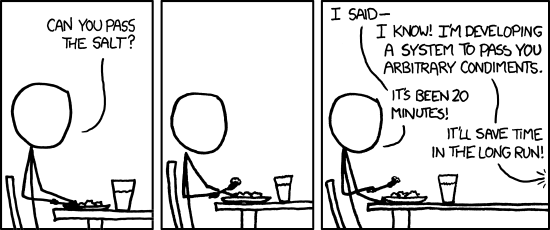

##The General Problem##

From xkcd

Now that you can write your own functions, you too will experience the dilemma of deciding whether to spend the extra time to make your code more general, and therefore more easily reused in the future.

Up To Schedule - Back To Make Incremental Changes I - Forward To Make Incremental Changes II