-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 9

/

Copy path20-visualisation2.Rmd

683 lines (523 loc) · 22.3 KB

/

20-visualisation2.Rmd

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

336

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

345

346

347

348

349

350

351

352

353

354

355

356

357

358

359

360

361

362

363

364

365

366

367

368

369

370

371

372

373

374

375

376

377

378

379

380

381

382

383

384

385

386

387

388

389

390

391

392

393

394

395

396

397

398

399

400

401

402

403

404

405

406

407

408

409

410

411

412

413

414

415

416

417

418

419

420

421

422

423

424

425

426

427

428

429

430

431

432

433

434

435

436

437

438

439

440

441

442

443

444

445

446

447

448

449

450

451

452

453

454

455

456

457

458

459

460

461

462

463

464

465

466

467

468

469

470

471

472

473

474

475

476

477

478

479

480

481

482

483

484

485

486

487

488

489

490

491

492

493

494

495

496

497

498

499

500

501

502

503

504

505

506

507

508

509

510

511

512

513

514

515

516

517

518

519

520

521

522

523

524

525

526

527

528

529

530

531

532

533

534

535

536

537

538

539

540

541

542

543

544

545

546

547

548

549

550

551

552

553

554

555

556

557

558

559

560

561

562

563

564

565

566

567

568

569

570

571

572

573

574

575

576

577

578

579

580

581

582

583

584

585

586

587

588

589

590

591

592

593

594

595

596

597

598

599

600

601

602

603

604

605

606

607

608

609

610

611

612

613

614

615

616

617

618

619

620

621

622

623

624

625

626

627

628

629

630

631

632

633

634

635

636

637

638

639

640

641

642

643

644

645

646

647

648

649

650

651

652

653

654

655

656

657

658

659

660

661

662

663

664

665

666

667

668

669

670

671

672

673

674

675

676

677

678

679

680

681

682

683

# Data visualisation {#sec-vis}

This chapter is based on Chapter 3 [*High Quality Graphics in

R*](https://www-huber.embl.de/msmb/Chap-Graphics.html) of the *Modern

Statistics for Modern Biology* book [@MSMB].

```{r env, message = FALSE, echo = FALSE}

suppressPackageStartupMessages(library("ggplot2"))

suppressPackageStartupMessages(library("dplyr"))

suppressPackageStartupMessages(library("Hmisc"))

suppressPackageStartupMessages(library("plotly"))

```

## Introduction

The **goal** of data visualisation is to

- interactively explore and understand data, i.e. *exploratory data

analysis*;

- to present and *communicate results*, whether as a preliminary

analysis or final results.

Our **learning objectives** are

- Familiarise ourselves with plotting in R using base graphics and

`ggplot2`;

- Understand the concepts behind the grammar of graphics and `ggplot2`;

- Learn how to visualise data along 1, 2 or more dimensions;

- Learn about `plotly`, one package for producing interactive

visualisations.

The difference between this chapter, and the [*Data

Visualisation*](ttps://uclouvain-cbio.github.io/WSBIM1207/sec-vis.html)

of the introductory WSBIM1207 course is that here we focus on

understanding and communicating data through visualisation, rather

than on the syntax of the plotting packages. Here are a couple couple

of [*visualisation horror picture show*](./horror.pdf) from a lecture

by Wolfgang Huber to illustrate what not to do.

Let's use the famous [*Anscombe's

quartet*](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anscombe%27s_quartet) data as

a motivating example. This data is composed of 4 pairs of

values, $(x_1, y_1)$ to $(x_4, y_4)$:

```{r anscombe, echo = FALSE, results='asis'}

knitr::kable(anscombe)

```

Each of these $x$ and $y$ sets have the same variance, mean and

correlation:

```{r anscombetab, echo=FALSE}

tab <- matrix(NA, 5, 4)

colnames(tab) <- 1:4

rownames(tab) <- c("var(x)", "mean(x)",

"var(y)", "mean(y)",

"cor(x,y)")

for (i in 1:4)

tab[, i] <- c(var(anscombe[, i]),

mean(anscombe[, i]),

var(anscombe[, i+4]),

mean(anscombe[, i+4]),

cor(anscombe[, i], anscombe[, i+4]))

```

```{r anstabdisplay, echo=FALSE}

knitr::kable(tab)

```

But...

While the *residuals* of the linear regression (see chapter

\@ref(sec-obj)) clearly indicate fundamental differences in these

data, the most simple and straightforward approach in *visualisation*

is to highlight the fundamental differences in the datasets.

```{r anscombefig, echo=FALSE}

ff <- y ~ x

mods <- setNames(as.list(1:4), paste0("lm", 1:4))

par(mfrow = c(2, 2), mar = c(4, 4, 1, 1))

for (i in 1:4) {

ff[2:3] <- lapply(paste0(c("y","x"), i), as.name)

plot(ff, data = anscombe, pch = 19, xlim = c(3, 19), ylim = c(3, 13))

mods[[i]] <- lm(ff, data = anscombe)

abline(mods[[i]])

}

```

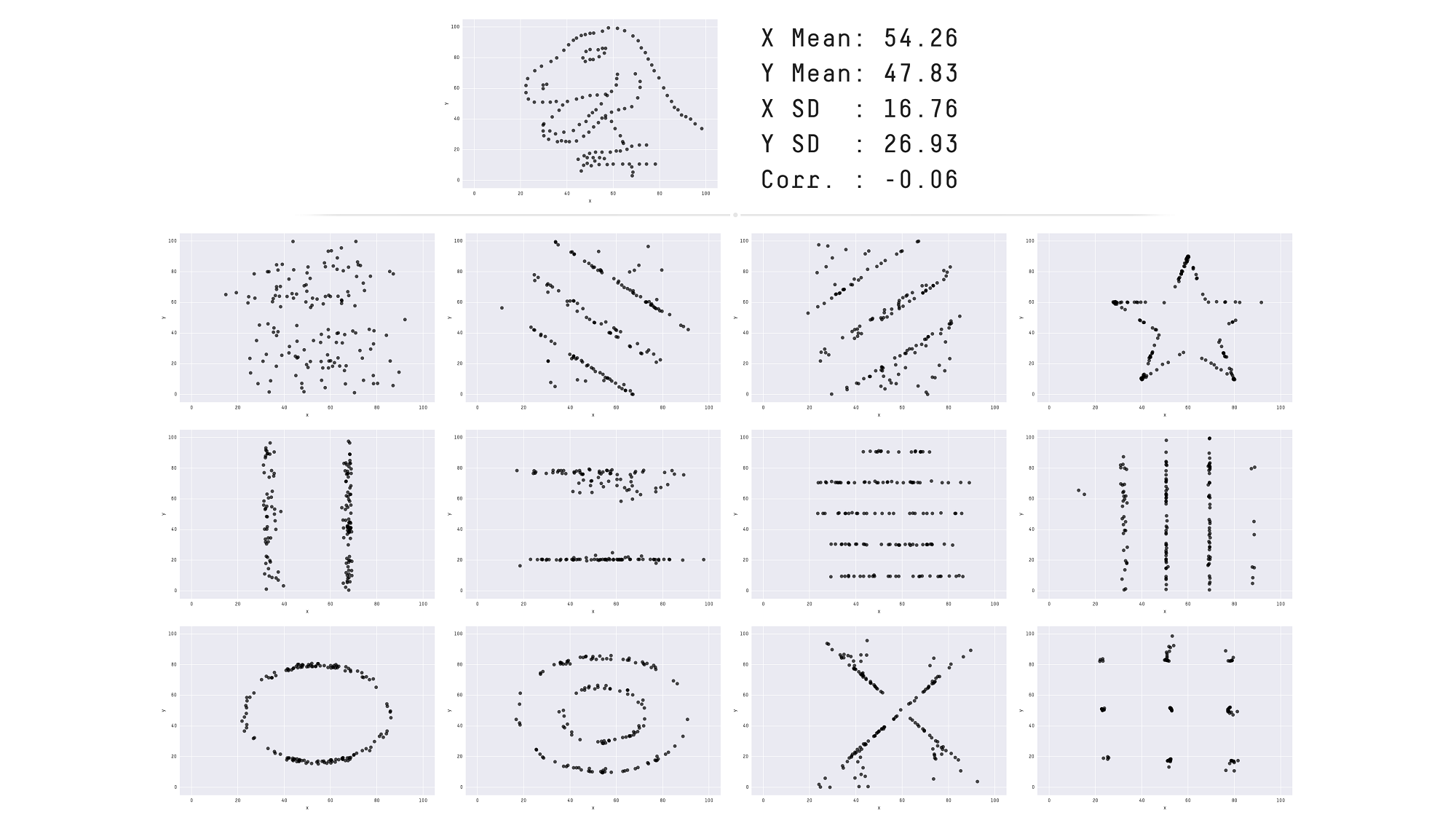

See also another, more recent example:

[The Datasaurus Dozen dataset](https://www.autodeskresearch.com/publications/samestats).

Throughout this course we will focus on producing visualisations that

will enable **understanding important features** of biomolecular data

or the effect of their transformation and analyses. With this in mind,

the beauty of the visualisations we will produce won't be assessed by

how visually attractive the figures are, but how they advance our

understanding the data. In the process of data exploration and data

analysis, we want to be able to quickly generate and interpret

figures. It is of course important to polish the graphics to make them

visually appealing and improve communication with the audience, once a

useful figure has been chosen as a means of communication.

An important aspect of data visualisation is data **manipulation**,

transformation and the format of the data: as seen in

[WSBIM1207](https://uclouvain-cbio.github.io/WSBIM1207/sec-dplyr.html),

its scale (see below) and normalisation of the data (see chapter

\@ref(sec-norm)).

A last feature of data that is intimately associated with its

manipulation and visualisation is its **structure**: long and wide

dataframes (as introduced in

[WSBIM1207](https://uclouvain-cbio.github.io/WSBIM1207/sec-dplyr.html)

or dedicated objects (see chapter \@ref(sec-obj)). Some visualisations

will be much easier when the data is formatted in a certain way.

## Base plotting

The default graphics system that comes with R, often called base R

graphics is simple and fast. It is based on the painter's model or

canvas, where different output are directly overlaid on top of each

other.

Below, we display the relation between the optical density of the

deoxyribonuclease (DNase) protein as measure by an enzyme-linked

immunosorbent assay (ELISA) assay for all observations.

```{r dnase, fig.cap = "The default base `plot` function on the `DNase` data."}

head(DNase)

plot(DNase$conc, DNase$density)

```

We can add some features on the plot, such vertical dotted lines for

all observed observations and customise the look and feel of the plot

by setting specific arguments to the `plot` function.

```{r dnase2, fig.cap = "Customising a base figure using function arguments and overlaying new graphical features."}

plot(DNase$conc, DNase$density,

xlab = "DNase concentration (ng/ml)",

ylab = "Optical density",

pch = 1,

col = "steelblue")

abline(v = unique(DNase$conc), lty = "dotted")

```

If we wanted to change anything to the figures, we would need to

repeat all the commands and modify accordingly. Any additional command

would be added to the existing canvas.

`r msmbstyle::question_begin()`

How would you produce a figure that differentiates the different runs

using base graphics?

`r msmbstyle::question_end()`

`r msmbstyle::solution_begin()`

```{r colbyrun}

plot(DNase$conc, DNase$density, col = DNase$Run)

```

`r msmbstyle::solution_end()`

`r msmbstyle::question_begin()`

Use the `hist` and `boxplot` functions to produce a

histogram of all optical densities and a boxplot of the densities

split by run.

`r msmbstyle::question_end()`

`r msmbstyle::solution_begin()`

```{r hist_boxplot, fig.width = 14, fig.height = 7, fig.cap = "The base `hist` and `boxplot` functions, the latter using the formula interface."}

par(mfrow = c(1, 2))

hist(DNase$density)

boxplot(density ~ Run, DNase)

```

`r msmbstyle::solution_end()`

The base graphics function are very effective to quickly produce out

of the box figures. However, there is no global overview and

parametrisation of the visualisation. The layout decisions have to be

made up upfront (and if not adequate, the figure needs to be redrawn)

and every aspect of the figure is customised locally as function

arguments.

More generally, base graphics functions will work with various inputs:

above we have worked with a `data.frame`, vectors and a formula. There

is no unified type of data across all functions which makes it

efficient for some types of data (if they match), but also very

heterogeneous in terms of interface, leading to a lot of customisation

code.

Finally, defaults, and colours in particular, are poorly chosen.

## The `ggplot2` package

**`ggplot2`** is a plotting package that makes it simple to create

complex plots from data in a data frame. It provides a more

programmatic interface for specifying what variables to plot, how they

are displayed, and general visual properties. The theoretical

foundation that supports the `ggplot2` is the *Grammar of

Graphics*[^gg]. Instead of producing the figure, the user defines and

assembles the visual components into an object that is the

displayed. There is a book about ggplot2[^ggbook] that provides a good

overview, but it is outdated. The ggplot2 web page

(https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org) provides ample documentation.

[^gg]: Wilkinson, Leland. 2005. The Grammar of Graphics (Statistics

and Computing). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag.

[^ggbook]: Wickham, Hadley. 2016. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data

Analysis. Springer-Verlag New York.

To build a ggplot, we will use the following basic template that can

be used for different types of plots:

```

ggplot(data = <DATA>, mapping = aes(<MAPPINGS>)) + <GEOM_FUNCTION>()

```

We need first to load the `ggplot2` package:

```{r ggload}

library("ggplot2")

```

- use the `ggplot()` function and bind the plot to a specific data frame using the

`data` argument

```{r gg0, fig.cap = "We have only specified the data, and there's nothing to display yet."}

ggplot(data = DNase)

```

- define a mapping (using the aesthetic (`aes`) function), by

selecting the variables to be plotted and specifying how to present

them in the graph, e.g. as x/y positions or characteristics such as

size, shape, colour, etc.

```{r gg1, fig.cap = "`ggplot2` can now generate the axes, ticks and ranges based on the data."}

ggplot(data = DNase,

mapping = aes(x = conc, y = density))

```

- add *geoms* – graphical representations of the data in the plot

(points, lines, bars). To add a geom to the plot use the `+`

operator. Because we have two continuous variables, let's use

`geom_point()` first:

```{r gg2, fig.cap = "Final figures with rendering of the data as a scatter plot."}

ggplot(data = DNase,

mapping = aes(x = conc, y = density)) +

geom_point()

```

`r msmbstyle::question_begin()`

Compare the `ggplot2` and base graphics version of the density

vs. concentration plot. Which one do you prefer, and why?

`r msmbstyle::question_end()`

It is possible to store the output of the `ggplot` function into a

variable that can be visualised by either typing its name in the

console or explicitly printing it (like any other variable).

```{r ggobj, fig.cap = "Saving and printing an object."}

gg <- ggplot(data = DNase,

mapping = aes(x = conc, y = density)) +

geom_point()

print(gg)

```

Let's immediately customise this visualisation to

- highlight how to re-use the `gg` object without repeating the

plotting code and

- how we can add additional (identical or different) *geoms* to a

plot.

```{r gg3, fig.cap = "Adding another `geom_point` with its own (local) aesthetics. "}

gg + geom_point(aes(colour = Run))

```

`r msmbstyle::question_begin()`

What do you think of the colours used to differentiate the different

runs above?

`r msmbstyle::question_end()`

`r msmbstyle::solution_begin()`

```{r ggex, fig.cap = "Setting the Run to a category by coercing it to a character, rather than a numeric."}

gg + geom_point(aes(colour = as.character(Run)))

```

`r msmbstyle::solution_end()`

Finally, we can model easily model and visualise the relation relation

between concentration and optical density using a *smoothing geom*:

```{r dnasmooth, fig.cap = "Modelling the relation between concentration and optical density."}

ggplot(data = DNase,

mapping = aes(x = conc,

y = density)) +

geom_point(aes(colour = as.character(Run))) +

geom_smooth(method = "loess")

```

<!-- Below is an example of more elaborated composition, overlaying points -->

<!-- and a non-linear *loess* regression. But first, let's load a object -->

<!-- containing microarray data from the `hiiragi2013df1` data. The data is -->

<!-- originally available from the -->

<!-- [`Hiiragi2013`](http://bioconductor.org/packages/release/data/experiment/html/Hiiragi2013.html) -->

<!-- package and describes the cell-to-cell expression variability followed -->

<!-- by signal reinforcement progressively segregates early mouse lineages -->

<!-- [@Ohnishi:2014]. -->

<!-- ```{r gg4, fig.cap = "Modelling the relation between the expression of X1426642_at and X1418765_at."} -->

<!-- library("rWSBIM1322") -->

<!-- data(hiiragi2013df1) -->

<!-- ggplot(hiiragi2013df1, aes(x = X1426642_at, y = X1418765_at)) + -->

<!-- geom_point(shape = 1) + -->

<!-- geom_smooth(method = "loess") -->

<!-- ``` -->

<!-- And, adding colours representing the different samples -->

<!-- ```{r gg5, fig.cap = "Modelling the relation between the expression of X1426642_at and X1418765_at and annotating samples."} -->

<!-- ggplot(hiiragi2013df1, aes(x = X1426642_at, y = X1418765_at)) + -->

<!-- geom_point(aes(color = sampleColour), shape = 19) + -->

<!-- geom_smooth(method = "loess") -->

<!-- ``` -->

## Visualising 1D data

Let's start by exploring some 1 dimensional visualisation. This is

very relevant for omics data such as transcriptomics or quantitative

proteomics, when contrasting the expression values across multiple

samples.

We will be using data from the

[`Hiiragi2013`](http://bioconductor.org/packages/release/data/experiment/html/Hiiragi2013.html)

package and describes the cell-to-cell expression variability followed

by signal reinforcement progressively segregates early mouse lineages

[@Ohnishi:2014].

```{r hiiragi}

library("rWSBIM1322")

data(hiiragi2013df1)

head(hiiragi2013df1)

```

First, we convert a microarray gene expression data to a data.frame,

fit for some `ggplot2` visualisation, focusing on genes Fgf4 (probeset

`X1420085_at`), Gata4 (`X1418863_at`), Gata6 (`X1425463_at`) and Sox2

(`X1416967_at`).

```{r pivot_longer, message = FALSE}

library("tidyverse")

genes <- dplyr::rename(hiiragi2013df1,

Fgf4 = X1420085_at,

Gata4 = X1418863_at,

Gata6 = X1425463_at,

Sox2 = X1416967_at) |>

select(Fgf4, Gata4,

Gata6, Sox2) |>

pivot_longer(names_to = "gene",

values_to = "expression",

everything())

head(genes)

```

### Histogram

```{r hist, fig.cap = "Distribution of the Gata4 expression"}

genes |>

filter(gene == "Gata4") |>

ggplot(aes(x = expression)) + geom_histogram()

```

### Box plots

```{r boxplot, fig.cap = "A boxplot of expression values."}

p <- ggplot(genes, aes(x = gene, y = expression, fill = gene))

bxplot <- p + geom_boxplot()

bxplot

```

`r msmbstyle::question_begin()`

Repeat the above figure replacing the boxes by violins using the

`geom_violin`. Which one do you think does a better job?

`r msmbstyle::question_end()`

`r msmbstyle::solution_begin()`

```{r violin, fig.cap = "A violin plot of expression values."}

vlnplot <- p + geom_violin()

vlnplot

```

`r msmbstyle::solution_end()`

See this post, [The Boxplot and its

pitfalls](https://www.data-to-viz.com/caveat/boxplot.html) for more

detail about boxplots and how to improve them using jitter, violin

plots, and information about the sample size.

### Dot plots and beeswarm plots

When the data aren't too large, it is also possibly to visualise all

points to get a sense of their distribution.

```{r jitter}

jtrplot <- p +

geom_jitter(aes(colour = gene)) +

theme(legend.position = "none")

```

In a dotplot, the position of the points along the y axis is

discretised into bins (set as 1/6 below) and the points are then

stacked next to each other.

```{r dot}

dotplot <- p + geom_dotplot(binaxis = "y", binwidth = 1/6,

stackdir = "center", stackratio = 0.75,

aes(color = gene)) +

theme(legend.position = "none")

```

The beeswarm algorithms tries to avoid overlapping points: if a point

were to overlap an existing point, it is shifted along the $x$-axis

by a small amount sufficient to avoid overlap.

```{r bee}

library("ggbeeswarm")

beeplot <- p + geom_beeswarm(aes(color = gene)) +

theme(legend.position = "none")

```

```{r showdots, fig.cap = "Showing all expression values using jittering (left), a dotplot (centre) and a beeswarn plot.", fig.with = 16, fig.height = 4}

library(patchwork)

jtrplot + dotplot + beeplot

```

### Density and ecdf plots

```{r dens}

densplot <- ggplot(genes, aes(x = expression, color = gene)) +

geom_density() +

theme(legend.position = "none")

```

```{r ecdf}

ecdfplot <- ggplot(genes, aes(x = expression, color = gene)) +

stat_ecdf() +

theme(legend.position = "none")

```

```{r, fig.cap = "Density and cumulative density functions of expression values.", fig.with = 12, fig.height = 6}

densplot + ecdfplot

```

### Summary

- **Boxplot** makes sense for unimodal distributions (see below).

- **Histogram** requires definition of bins (width, positions) and can

create visual artefacts especially if the number of data points is

not large.

- **Density** requires the choice of bandwidth; obscures the sample

size (i.e. the uncertainty of the estimate).

- **ecdf** does not have these problems; but is more abstract and

interpretation requires more training. Good for reading off

quantiles and shifts in location in comparative plots.

- **beeswarm**: for up to a few dozens of points, just show the data.

## Number of modes

The number of modes of a distribution depends on scale transformation

of the data.

```{r sim, fig.cap = "Histograms of the same data without (left) and with (right) log-transformation."}

sim <- data.frame(x = exp(rnorm(n = 1e5,

mean = sample(c(2, 5),

size = 1e5,

replace = TRUE))))

p1 <- ggplot(sim, aes(x)) +

geom_histogram(binwidth = 10, boundary = 0) +

xlim(0, 400)

p2 <- ggplot(sim, aes(log(x))) +

geom_histogram(bins = 30)

p1 + p2

```

This also applies to density plots.

## Visualising 2D data

```{r sc1, fig.cap = "Scatter plot comparing the expression of a wild-type vs. FGF4 KO."}

data(hiiragi2013df2)

head(hiiragi2013df2)

scp <- ggplot(hiiragi2013df2,

aes(x = `59 E4.5 (PE)`,

y = `92 E4.5 (FGF4-KO)`))

scp + geom_point()

```

`r msmbstyle::question_begin()`

The over-plotting of the dots stops us from learning anything about

the density of the different regions of the plot. Use the `alpha`

parameter to `geom_points` between 0 (full transparency) to 1 (opaque,

default).

`r msmbstyle::question_end()`

`r msmbstyle::solution_begin()`

```{r scp2, fig.cap = "Transparency can help distinguish regions of different densities."}

scp + geom_point(alpha = 0.1)

```

`r msmbstyle::solution_end()`

```{r scp3, fig.cap = "Focusing on contours rather that individual values."}

scp + geom_density2d(h = 0.5, bins = 60)

```

```{r scp5, fig.cap = "Local density summaries."}

scp + geom_hex()

```

## Visualising data along more dimensions

When visualising data along additional dimension, we can parameterise

the points by setting their shape, colour, size and transparency, that

can be set with point aesthetics such as `fill`, `color` (or

`colour`), `shape`, `size` and `alpha`.

A very powerful way to represent data along additional dimensions is

facetting, i.e. producing sub-plots for different subsets of the

data. Below, we first re-annotate the data using some regular

expressions

```{r facet1, fig.cap = "Different sub-plots for different lineages using colours (left) of facets (right) to distinguish the different lineages."}

p1 <- ggplot(hiiragi2013df1, aes(x = X1426642_at, y = X1418765_at, colour = lineage)) +

geom_point()

p2 <- ggplot(hiiragi2013df1, aes(x = X1426642_at, y = X1418765_at)) +

geom_point() +

facet_grid( . ~ lineage )

p1 + p2

```

```{r facet2, fig.cap = "Different sub-plots for different lineages and embryonic stages."}

ggplot(hiiragi2013df1,

aes(x = X1426642_at, y = X1418765_at)) +

geom_point() +

facet_grid( Embryonic.day ~ lineage )

```

`r msmbstyle::question_begin()`

Use facets to visualise the distribution of the four Fgf4, Gata4,

Gata6 and Sox2 genes in the `genes` data using histograms.

`r msmbstyle::question_end()`

`r msmbstyle::solution_begin()`

```{r hist2}

ggplot(genes, aes(x = expression)) +

geom_histogram() +

facet_wrap(~ gene)

```

`r msmbstyle::solution_end()`

## Interactive visualisation

```{r plotly0}

scp <- ggplot(hiiragi2013df2[1:100, ],

aes(x= `59 E4.5 (PE)`, y = `92 E4.5 (FGF4-KO)`))

scp2 <- scp + geom_point()

```

Once we have stored ggplot object in a variable, we can simply pass it

to the `plotly::ggplotly` function to generate an interactive figure.

```{r plotly, eval = FALSE}

library("plotly")

ggplotly(scp2)

```

See https://plot.ly/r for examples of interactive graphics online.

## Additional exercises

`r msmbstyle::question_begin()`

Load the `barley` data that comes with the `lattice` package (that is

already installed on your computer). The data describe the yield from

a Minnesota barley trial as a data frame with 120 observations on the

following 4 variables.

- `yield` Yield (averaged across three blocks) in bushels/acre.

- `variety` Factor with levels `Svansota`, `No. 462`, `Manchuria`,

`No. 475`, `Velvet`, `Peatland`, `Glabron`, `No. 457`, `Wisconsin No. 38`

and `Trebi`.

- `year` Factor with levels `1932` and `1931`.

- `site` Factor with 6 levels: `Grand Rapids`, `Duluth`,

`University Farm`, `Morris`, `Crookston`, `Waseca`.

Familiarise yourself with the data

`r msmbstyle::question_end()`

```{r bar1, echo = FALSE}

library(lattice)

data(barley)

```

`r msmbstyle::question_begin()`

Visualise the yield for each variety on all site in 1932 and 1931

using `ggplot2`. Try to generate a figure on your own. If you

struggle, discuss with your fellow students. If you need additional

help, or as a check, execute the code in the `barley` manual page

example.

`r msmbstyle::question_end()`

```{r, echo = FALSE, include = FALSE}

ggplot(barley, aes(x = yield, y = variety, colour = year)) +

geom_point() +

facet_grid(site ~ .)

```

`r msmbstyle::question_begin()`

Can you spot an issue with the data?

`r msmbstyle::question_end()`

`r msmbstyle::question_begin()`

Write a function named `(gg)plot_probe_sets` that takes two probe sets

and the `hiiragi2013df1` data (from the `rWSBIM1322` package) as input

and produces a scatterplot. Your function should test if the provided

probe sets are valid before producing the plot and inform

otherwise. Below are some example outputs.

```{r plot_probe_sets, echo = FALSE}

plot_probe_sets <- function(x, y, data = hiiragi2013df1) {

stopifnot(x %in% colnames(hiiragi2013df1)[1:6])

stopifnot(y %in% colnames(hiiragi2013df1)[1:6])

plot(data[, x], data[, y], xlab = x, ylab = y)

}

ggplot_probe_sets <- function(x, y, data = hiiragi2013df1) {

stopifnot(x %in% colnames(hiiragi2013df1)[1:6])

stopifnot(y %in% colnames(hiiragi2013df1)[1:6])

ggplot(data = hiiragi2013df1,

aes(x = .data[[x]], y = .data[[y]])) +

geom_point()

}

```

```{r visfun, fig.width = 8, echo = TRUE}

plot_probe_sets("X1426642_at", "X1420085_at", data = hiiragi2013df1)

ggplot_probe_sets("X1426642_at", "X1420085_at", data = hiiragi2013df1)

try(plot_probe_sets("X1416967_at", "123_at"))

```

`r msmbstyle::question_end()`